INDONESIA TRAVEL JOURNAL – continued

PART 2a: FLORES AND THE KOMODO ISLANDS June 23-30, 2014

Callyn Yorke

Link to Part 1: Singapore and Sulawesi

Link to Part 2b: Bali

Link to Flores and Komodo Annotated Bird List

I was about ten when I learned of a distant land with giant lizards that could rip someone’s head off with one bite. They were called dragons, Komodo Dragons, and they were an unlikely candidate for a house pet. The dragons of Komodo were real, alright. Our fifth-grade encyclopedia had a full page of text and photos of the beast.

Several decades passed before I came close to fulfilling a dream of actually being face to face with a Komodo Dragon. That day finally arrived as our thirty-foot wooden boat pulled into a slot at a small, crowded dock at Loh Buaya on the island of Rinca.

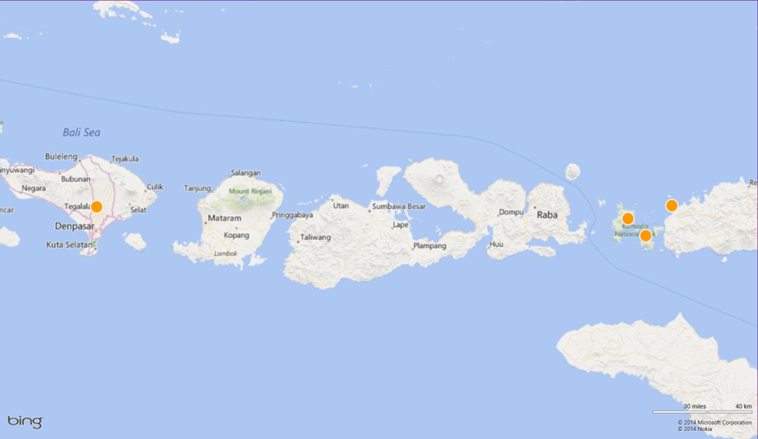

Rinca is a famous place these days. As one of the larger islands in the Flores-Komodo archipelago of eastern Indonesia, it is one of only two places on the planet you have a good chance to see the largest living lizards in their native habitat. A few miles away is the even more famous island of Komodo, the fabled kingdom of the dragon. Thousands of tourists visit these desolate, semi-arid islands every year. Today, my guide Fidelis and I are lucky enough to be among a handful of scheduled, prepaid visitors, all anxious to have a close encounter with a dragon, and of course, live to tell about it.

I immediately had a tingly feeling about this strange, quiet place. It was a warm, humid day with gentle southeasterly winds caressing the barren hills around us. It looked like a scene from a 1960’s Hitchcock thriller. Something extraordinary was about to take place here. I strapped on my camera and binocular. I felt like fifth-grader ready for the adventure of a lifetime.

Rinca is part of Komodo National Park, established around 1980. Nowadays, visitors are not allowed to trek on the island unsupervised. That rule came about as a result of number of close calls, including a fatality on Komodo Island. The park service leaves little to chance. Everything is carefully managed here — the number of visitors, education of park rangers, maintenance of walkways and trails, collection of entrance fees (including a camera fee – extra for video cameras), and of course, the celebrity dragons. By the latest count, about 2,500 of them occur on Rinca; Komodo Island, slightly larger than Rinca, has a about 2,800 dragons. Clusters of wooden buildings, pathways of crushed coral, all give Rinca the initial appearance of a South African game reserve. But, watch your step here, the dragons are entirely wild and always on the lookout for the next meal.

Near the landing at low tide we passed a troupe of Long-tailed Macaques eating crabs in a mangrove. They looked up at us and kept eating. Near the end of a long walkway of crushed coral, we were greeted by a ranger, clutching a seven-foot forked stick. Evidently, like elementary schools in the 1800’s, the island inhabitants know and respect the stick. I wonder how long it would take elephants and lions in Africa’s parks to realize that a forked stick is about as threatening as any other small piece of wood. Komodo Dragons may be opportunistic and adaptable, but most of them, thankfully, appear to need more time for a breakthrough with this problem.

The current dragon population densities on Rinca and Komodo would likely be impossible without introduced pigs, deer and water buffalo. Prior to the arrival of man and his domestic side-kicks, the dragon population was probably significantly smaller than today. Of course I am just speculating. We really don’t know anything about the original natural history of these islands.

Exactly what dragons ate in those days is unknown. Since dragons are both predators and scavengers, as are their closest relatives in the monitor lizard family, they probably survived by inactivity, lowering their metabolism during the months between meals. Native prey on their menu may have included Long-tailed Macaque, Cuscus, an assortment of terrestrial bird species (e.g. members of the widespread gallinaceous and megapode families), and smaller items such as insects, crustaceans, fish, snakes and lizards, including each other. Death from cannibalism and starvation continues to be common among the dragons on both islands. Komodo Island villagers are allowed by the government to harvest the teeth and other parts of dead dragons to fashion trinkets and costume jewelry for tourists. Not surprisingly, the Indonesian government has recognized the region as a World Heritage site. Here, quite literally, dragons rule. The government is banking on it to stay that way.

Smiling proudly, our assigned ranger-guide said, in recognizable English, we had arrived at an extremely fortunate time. Several dragons were feeding nearby the park headquarters.

With great anticipation, Fidelis and I mindfully strolled along a stony trail past a cluster of small wooden shacks. The ranger casually pointed out a Green Tree Viper, which was suspended motionless on a small, leafy branch near the base of a tree. Owing to its small size (about twelve inches in length) and perfect leaf-matching coloration, it might have been easily overlooked had the ranger chosen to ignore it.

Not more than thirty feet from this lethargic but deadly little snake, a young Komodo Dragon was ripping pieces of putrid flesh from a Timor Deer carcass, which looked and smelled to be at least a week old. Here it was –my very first encounter with the mythical beast! Even though this one was no bigger than a rat terrier, I must have captured fifty images of the busy little guy, worried it might be the only Komodo Dragon we would see at close range.

We continued walking warily through the thickets and tall grass. An adult dragon watched us a few yards away. This individual was a no-nonsense, full-grown male, perhaps weighing 200 pounds, sedentary yet alert and responsive to my attempts to obtain a close-up photo. The ranger cautioned me and I stepped back a few feet from the beast, clicking off two dozen frames as fast as my Nikon D3X SLR and 80-400 AF VR lens would work. Like a beach comber finding a pirate’s treasure, there was a tingling sensation of getting away with something that must be either highly illegal or at least ill-advised.

Its amazing how fast one habituates to risk. Superficially, there was nothing particularly frightening about these oversized lizards. For the most part they were habituated to humans, silent and slow-moving. Indeed, the dragons appeared to casually disregard our presence, save an occasional tongue-flick. It might be possible to become rather bored here after being in proximity to these gentle giants. Big mistake. These are not passive herbivores, like giant tortoises. Complacency around these top-of-the-food-chain reptiles could get somebody killed in a most horrid way. Just one look those wrinkly poker faces, says “game over” for the unwary. I took a few quick steps closer to the ranger, who carried our only means of defense, the educational forked stick. I wondered when the last time was he had to use it. Maybe he was like a cop who never had to shoot anyone, but was always ready if things went south.

Probably sensing our excitement building, the ranger hastened up a grassy slope overlooking a ravine and a group of about six tourists, all intently staring down at something we couldn’t yet see. One of the other guides was wearing a surgical mask. Were they afraid of breathing on the endangered dragons?

About forty feet from us several adult dragons were engaged in a feeding frenzy. At first, I couldn’t identify exactly what it was they were plunging into. One partly amputated limb, blackened with decay, stiffly pointed skyward; below it huge, bloated and muddied torso. Our guide said it was a two-week old water buffalo carcass, now fully marinated in a delicious blend of mud, lizard saliva and spicy aromas emanating from every family of microbe known to science. Yummy.

The mud-caked dragons literally dove into the massive carcass, ripping off strips of flesh using serrated shark-like teeth and powerful forelimbs with grizzly bear-sized claws. They dragged their swollen bellies around with surprising agility. We learned from the ranger that adult dragons may consume forty pounds of meat in one feeding. These three adult females all seemed to get along without the slightest territorial dispute, or producing so much as a rude burp or fart. In fact, there was little or no interaction among them, as though the dining table rules had already been worked out. They simply ripped and clawed at will, sometimes raising their heads, looking at us, flicking a long pink tongue, and continuing with their meal. The wind direction changed and suddenly the stench was inescapable. Small wonder the park rangers wear masks, though I doubt anything short of holding one’s breath would offer much relief. Fascinating, captain. Time to beat a hasty retreat through the brush and back to the main trail for some fresh air.

Although they are frighteningly powerful animals, Komodo Dragons seldom kill large prey in a single encounter. Like a viper, these venomous reptiles are patient and watchful. Sneaking up on unwary buffalo, they preferentially nip the groin area, inflicting superficial wounds, a personal violation that I imagine must be rather annoying. Regardless of the size or strength of the prey, some time later the poor victim takes its last gasp, bleeding excessively due to anticoagulant protein (i.e. venom) secreted from ducts between the serrated teeth of the lower mandible, together with lethal cocktail of bacteria, cultured to evolutionary perfection in a dragon’s mouth.

The Komodo Dragon takes dental hygiene and bad breath to a entirely new level. Courtship among them must be rather unpleasant. “Sweety, how about a smooch please.” Moreover, judging from the buffalo fiesta we just watched, frothing buccal cavities are overflowing with pathogens in every dragon’s smile. After attending the Komodo pan-generational, do-or-die, biochemical school of natural selection, these lizards, like saltwater crocodiles and vultures, probably evolved a fail-safe immune defense system – an exciting possibility for immuno-pharmacological research with medical applications (e.g. Gila Monster venom protein derivatives are used to treat diabetes). Perhaps one day physicians will be prescribing Komodo Dragon plasma injections instead of Penicillin.

KOMODO ISLAND

Having all the dragon eye-candy I could possibly consume on Rinca Island, our next stop in our two-day journey was Komodo Island. My focus would shift back to birds and other wildlife reported to be common on Komodo Island. In fact, the dragons could be a bit of a nuisance to birders, who usually spend a lot of time looking up in the trees rather than at the ground.

After three hours of slow going (about five knots) and navigating by dead reckoning, the Spider’s captain brought us to a quiet bay opposite the Komodo Island village, inhabited by about 1,500 Muslims. We spent the remainder of the evening aboard the boat. I was informed by Fidelis that there wasn’t sufficient daylight left for an island landing. Some village boys selling souvenirs appeared alongside us paddling their small dugouts.

Another, larger wooden vessel was nearby, containing an Indonesian crew and two Westerners. Some friendly shouting began between the two crews. I sat on a bench at our dining table, as the the first mate prepared our evening meal of rice, fish, vegetables and fresh fruit. There wasn’t much of interest for me to do because we were anchored a little too far offshore to observe birds and other wildlife known to inhabit the island. Meanwhile, seizing a business opportunity, several more villagers paddled out with their locally made wares; one dude had a few bottles of Bintang beer for sale. These folks knew their customers well and, unlike us, they had come prepared.

Our neighbors tossed some scraps overboard and suddenly there appeared a handsome adult Brahminy Kite circling above us. I thought of something that, as a conservation biologist, probably should never have crossed my mind (though I wouldn’t hesitate to capitalize on the situation, should someone else instigate it). Welcome to wildlife photography by chumming. Nature faking, if you don’t mind.

At my request, the first mate tossed a small piece of fish overboard. Holding my camera, I braced myself with a wide stance like a seasoned professional photographer, whom had spent months hiding in a blind, waiting for that rare instant of incomparable splendor, one brief glimpse and a few dozen digital images of some rare bird that few people have ever seen.

With rapid-fire shutter action, I captured a close-up, recognizable image of one of the commonest scavenging birds of prey in the entire Indo-Malayan region. That was almost good. What else is there to do around here?

The people in the boat next to us were amused. They were a husband and wife from Salt Lake City who invited me to have a beer with them aboard their spacious cabin cruiser. I crawled over the rail as our boats rubbed together, stern to stern. We talked for quite awhile, awaiting our separately prepared meals. To help prevent our new friendship from drifting apart, I guess the crew thought it best to tie our boats together.

The friendly couple from Utah were the first Americans I had met in Indonesia. This part of the world had evidently been off the American travel agency radar. It was good to chat with them and learn of their adventures. Like most Westerners I met in Indonesia, these two were well-traveled and full of interesting anecdotes.

Coincidentally, another little travel story was unfolding that evening. Their boat’s old diesel motor was reportedly running poorly. No surprise, really. Based on a few hours aboard the Spider, I predicted that most of these antique two-cylinder inboard engines, like some of the nearby volcanoes, might explode at anytime. With every labored piston stroke, the entire craft vibrated and shook, sending objects on the table sliding off to the floor and rendering double vision when I tried to identify a distant bird with a binocular. To the untrained ear, even a major engine malfunction on one of these boats (e.g. loose crankshaft or a lost cylinder) could easily go unnoticed.

if I had translated Bahasa Indonesia correctly, the crew of the USS Utah had neither tools nor spare parts to effect repairs. I related my conversation with the Indonesian crew to the Salt Lake City couple, who seemed as surprised I spoke Indonesian as they were mildly horrified by the news. Keep in mind that by now their trash can was nearly full of empty Bintang Beer cans.

At top speed (maybe seven knots with the wind behind us) we were a good four hours away from the nearest port at Labuanbajo, Flores. It was entirely possible my new friends could be stranded here for a couple of days. Oh well. We sipped our beer and contemplated the island life-style. There definitely could be worse places in the world to be stuck, than among these interesting, scenic islands. We had a good laugh at the comedy of their predicament. Actually, they could have returned on our boat if necessary. The crew even joined in the laughter. Clearly, they recognized we were all in the same boat, just south of Gilligan’s Island.

Whatever the mechanical problem was, their boat engine started up the following morning at 5:00AM, soon after the call to prayer in the adjacent village, and motored slowly away in the direction of Flores. Evidently, the diesel engine fixed itself overnight.

Sleeping on a small boat in a bunk that was too short even for someone of my modest height, took some tossing and turning to get comfortable. The problem was whichever way I turned, the boat always seemed to roll in opposition. The waves rocked and slapped the boat gently for the first few hours, then subsided. I left my cabin door ajar for improved air circulation, which also allowed me to drift off to sleep gazing at vaguely familiar constellations.

The following morning I awoke to the mosque loudspeaker calling the faithful to prayer, the sounds wafting hypnotically over the bay. It was dead calm and pitch black outside. I couldn’t imagine pulling myself together at that time in the morning for any reason, short of missing a flight or a rare bird. The only move I had was to just lie in the bunk and wait a half an hour for daylight. We were scheduled to have breakfast enroute to Komodo Island and land there at 0700 hrs..

As it turned out, dragons were scarce on the part of Komodo Island we visited. Only one individual was found loitering around a small wooden building. Even if someone had told me that prior to our departure, I would still have gone to the mysterious island. The power of legend is amazing indeed.

Everything went as planned that morning. I suggested we take the longest of three maintained trails on the island; the young ranger hesitantly agreed, asking if I had brought enough water. I nodded, anxious to get going. Fidelis, my guide from the company that had made the initial arrangements in Labuanbajo, wanted to tag along. Not sure he was in agreement with taking the long, three-hour route. We emphasized to the ranger that I was interested more in finding birds than dragons. He seemed to understand and we headed for the trail without further discussion.

Most of the birdlife, it turned out, was conveniently close to the park headquarters which was a short walk from the jetty. But because we had chosen the less frequented “long trail” we soon found ourselves scrambling up a steep hill overlooking the harbor. I had sweated through my shirt and trousers and my bottled water supply was finished. I realized why no one else among the dozen or so other tourists, had chosen this particular trail. It would have been a rigorous cardio workout, even without all of the heavy optical equipment dangling from my neck. In about an hour we were just below the summit of Rudolph Hill, catching our breath and enjoying the fruits of our effort, a magnificent view of the forested valley and harbor below.

Rudolph Hill was named in honor of a European gentleman who went trekking here alone in 1974 and was never seen again. What was found were pieces of clothing, his glasses and camera. The dragons had apparently consumed everything else.

I gazed down to the sparkling deep blue sea below us, realizing that this may have been one of the last sights poor Rudolph had enjoyed before his untimely death. No one but Rudolph knows exactly what happened, but anyone who has observed the eating habits of dragons, might readily imagine there could be few forms of death more horrible than to be torn to pieces by those powerful, voracious beasts. Small wonder the park service requires everyone on the island to go with a ranger carrying a big stick.

The lowlands around park headquarters had some bird species I was really keen to see. One of those is most certainly of Australian origin. I was excited when we heard the critically endangered Yellow-crested Cockatoo making its harsh calls in a tall tree above us. Got a few shots of it before it flew away, in classic cockatoo fashion, sounding quite pissed off.

Cockatoos are almost completely confined to Australia, where they are common and conspicuous members of the avifauna down under. Four species of Cockatoo occur in eastern Indonesia, though most are local and all are doubtless on the brink of extinction. Habitat loss and other anthropogenic factors are pushing these species into the few remaining areas of suitable habitat in Wallacea.

The fact that these essentially Australian birds are found in the eastern Indonesian archipelago, strongly suggests the latter was more or less connected to Australia, or at least closer in proximity than the islands are today. Falling sea levels and plate tectonics can account for most but not all of the present and historical distributions of animals found in Indonesia and Australia. Other factors (discussed earlier in my notes on Bunaken Island, Sulawesi) such as dispersal capability of the species, resource requirements (generalists have advantages; specialists are at a disadvantage) and initial size and genetic composition of the colonizing population, are variables that interact quantitatively in biogeographical ecology models. Elegant equations attempt to predict the probability that a particular island will have a particular fauna at a specific point in time. But as every serious student of Ornithology knows, most birds fly and none read range maps. Cockatoos don’t worry about solving for X and Y, their ancestors simply colonized and recolonized, survived, multiplied and perhaps sometime in the last few thousand years, differentiated into a distinctly separate species from their closest relatives in Australia.

A few other birds on Komodo with Australian affinities include representatives of the megapodes and friarbirds. The former are shy and difficult to see as they run away quickly into the thickets. The latter, friarbirds, are a little easier to observe. A Helmeted Friarbird made an appearance for a brief photo shoot. That was a another Indonesian life bird for me.

Moments prior to our departure from Komodo Island, two more sought after birds made an appearance, Green Junglefowl, a close relative of the domesticated Asian Jungle Fowl, and an endemic Wallacean Drongo. Excellent!

The return trip to Labuanbajo, Flores took about four hours, as anticipated. Items of interest along the route included a flock of Greater Crested Tern diving on schools of silvery fish, possibly mackerel. A little out of my camera range but nonetheless thrilling. Around us in certain areas were mysterious whirlpools of strong current, sometimes near small islands, sometimes far out to sea, causing the captain to pay close attention to our heading. These powerful and often unpredictable currents bring nutrients to the surface, resulting in spectacularly large schools of fish, such as manta rays and sharks. According to dive magazines and travel advertisements “Some of the best diving in the world is found here.” I didn’t have an opportunity to verify that particular legend on this trip, though I am fairly sure it is true. The remarkable diversity of marine life here is ultimately due to the complex and dynamic Australo-Asian oceanographic topography. These are some of the defining regional features of Wallacea.

Alfred Russell Wallace was one of the foremost British field biologists of the late 1800’s. He traveled extensively in the Indo-Malayan region, collecting specimens for the British Museum and keeping notes on the distribution of the creatures he encountered. More than two hundred species of animal bear his name. Additionally, Wallace’s observations that the intermediate islands of Indonesia (e.g. Sulawesi, Lesser Sundas and Moluccas) contained a unique mixture of Asian and Australian species, have subsequently been incorporated into modern biogeographical teachings. Thus, the islands west of Lombok (e.g. Sumatra, Borneo and Bali) contain animals of Asian origin (e.g. Hornbills, Woodpeckers, Drongos); whereas the islands eastward (e.g. Lombok, Sulawesi, Flores) contain, in varying proportions, interesting mixtures of Australian and Asian faunas. The deep water and swirling oceanic currents dividing those two biogeographical regions (i.e. the Lombok Straits) form the boundary known as Wallace’s Line.

Recently, Alfred Russell Wallace has been returned to the international spotlight. Bill Bailey, a British actor-comedian-musician, produced a delightfully informative biographical sketch of Wallace, by actually retracing some of Wallace’s journeys through Indonesia. Refocusing attention on Alfred Russell Wallace’s amazing work, Mr. Bailey single-handedly insured Wallace would be given all the honor and prestige almost exclusively owned by his counterpart, Charles Darwin. In the final dramatic scene of the film, shot on location at the British Museum of Natural History in London, a large portrait of Wallace was unveiled, and ceremoniously placed on the wall, adjacent to that of Charles Darwin. The two-hour BBC documentary is a must-see for anyone planning a visit to this region. Here’s the link to Bill Bailey’s two-part documentary on Alfred Russel Wallace:

A side note about traveling Indonesia aboard wooden boats. I have been around boats as long as I can remember. My dad had some boats custom built for water sports; others he bought second-hand for daily use. We had a summer home in the San Joaquin Delta of Northern California, and nearly everyone there, including kids my age, had a boat.

Of the many things I learned about operating boats as a youngster, was that there is actually a NUMBER ONE RULE. That is, Dude, remember to put the transom plug in before launching. Another important rule is to always watch where you’re going. I guess my dad thought it best to let me figure those things out on my own.

So when I arrived at the Labuanbajo harbor to board an unnamed wooden skiff bound for the Komodo Islands, I conducted a brief inspection of the craft and found it generally to be of sound construction, water tight, clean, well-organized and just about big enough for the four of us to move about on it single file without someone tumbling overboard.

The captain and first mate, who spoke no form of English whatsoever, smiled with confidence. They showed me the dining area, two sleeping berths and a head boasting a western-style toilet. There was a new life jacket still in the plastic wrapper next to my bunk bed. I saw nothing of the sort for Fidelis, who, like most Indonesians, probably couldn’t swim. I suppose if the Spider floundered, Manumundi Tours of Labuanbajo, would have expected Fidelis and the crew to go down with the ship in honorable fashion

There were two sleeping berths with bunk beds, so Fidelis and I each would have our own private berth. Everything looked ship shape. A few items were unsurprisingly absent – a compass, radio, flare gun and inflatable life raft. Those things were a bit too upscale for the boat’s owner, and generally regarded as unnecessary among locals. But the most troubling missing item was the boat’s name.

Half way through our journey, when the first mate set the main sail, I had a name for our boat: The Spider. The tattered old nylon sail had one embossed on it. Perfect. Like Jack London’s novel Sea Wolf, I was captive aboard a strange boat with a scary name.

I suppose Indonesians aren’t much interested in personifying their boats, as are other cultures around the world. That’s rather surprising, since these vessels are painstakingly constructed by hand with simple tools, following traditional methods used for hundreds of years. Each plank is cut and shaped to fit perfectly together like a jigsaw puzzle, so that, when finished these boats can be used day after day, year after year on the open ocean. Who knows how many wives filed for divorce while their husbands labored to build such fine ships? Then they had to keep building more to make the alimony and child support payments. And so the tradition continues.

The initial launch of a large vessel (e.g. 60 ft.) is also done entirely by hand with logs, planks, ropes and pulleys. Sometimes the launch takes weeks to complete, progressing only a few inches each day. You would think at least they could then come up with a name to commemorate such an effort, like Bertha Baby, Ubitch or maybe Waow (actually the latter name was painted on one of the boats shown in the images below).

A boat to an Indonesian is like a car to a Californian – an indispensable mode of transportation. And Indonesians arguably make the finest ocean-going wooden vessels in the world. The center for Indonesian boat building is south of Makassar on the island of Sulawesi. There, using traditional methods, some truly stunning wooden sailing vessels are produced and sold to people throughout the world. I was so impressed with the quality of workmanship of these hand-made vessels, I may have ended up with almost as many images of Indonesian boats as I have of their birds.

The larger ships (e.g. > 40 ft.) are often hired by travelers for a live-aboard experience. I have always wanted to do this. Maybe next time. Some of the best dive sites are known to these crews, and they may often have the place all to themselves for a few days. Sign me up.

_____________________________________________________

Link to FLORES AND KOMODO ANNOTATED BIRD LIST Callyn Yorke 2014