INDONESIA 2014

Callyn Yorke

Introduction

The initial part of the journey to Indonesia involved three international flights, LOS ANGELES to TOKYO; TOKYO to SINGAPORE; SINGAPORE to MANADO, SULAWESI – a total flight time of about nineteen hours. The first flight was nearly eleven hours; the following two, about half as lengthy (i.e. 5.5 hrs. and 2.5 hrs. respectively). Northern Sulawesi remained as the last region of Indonesia’s largest islands I had not yet visited.

For the second part of the journey, I would travel by air from Manado, Sulawesi to Jakarta, Java – then short flights to Bali and Lubuanbajo, Flores. According to maps and travel reports, it appeared Lubuanbajo was the most convenient point of departure for the Komodo Islands.

Although I was familiar with Bali and several of the Lesser Sunda islands from travels in the mid-1970’s, Flores and Komodo would be entirely new destinations. With great anticipation, I expected an opportunity to observe and photograph the biggest, scariest lizard in the world, the legendary Komodo Dragon. Unsure which part of this journey would be the most exciting, my travel itinerary would likely be filled with delightful surprises; in that regard, I was not disappointed. Link to Part 2: Flores, Komodo and Bali

____________________________________________________________

PART 1: Singapore, Bunaken Island and Northern Sulawesi June 3 – 21, 2014

June 3-6: L.A. > Singapore > Bunaken Island

Here’s an anecdotal summary of my first three days of the journey, from which were sent email dispatches to family and friends in the USA (quotation marks). Some of the digital images I obtained were included.

“I arrived in Singapore a few minutes after midnight, following an alarmingly turbulent flight from Tokyo. Imagine a six-hour, Northridge earthquake. Even the flight attendants, usually unshakably composed, looked rattled. It was a relief to finally be on solid ground.

When I found my hotel in the old district of ‘Little India’, the receptionist, with a heavy British-Indian accent, informed me that check-in time was 1400 hrs. and that he was, “very sorry, Sir,” no rooms were yet available. He kindly called a nearby hotel and reserved a room for me, I guess so that I wouldn’t be tempted to sleep in his hotel lobby. I wheeled my two 50 lb. bags down a quiet street, passing an Indian fellow asleep on the sidewalk in front of Hotel 81. There, a Chinese receptionist quickly accepted a few US dollars and handed me a room key. The hotel was quite busy at that late hour, mostly with young lovers coming and going.

I slept soundly, though briefly in a tiny, dark, frigid room without windows – like a space capsule acclimation experiment I remembered from a documentary film. At precisely 0430 hrs., I packed up my gear, checked out of Hotel 81, and wheeled my stuff back along a quiet street to the Sandpiper Hotel, my original destination.

A different clerk was there and he graciously took my bags into storage for the day. He hailed a taxi and directed the driver to the Singapore Botanical Gardens (SBG), where I planned to spend the day. SBG opened at 0500 hrs., presumably so that travelers and other dislodged individuals could be somewhere peaceful and safe, two hours before dawn.

Public health and safety are of primary concern in Singapore and laws are strictly enforced. Throughout the city, signs remind folks and their pets of proper and improper behaviors.

My camera, lenses and binocular, chilled as if they had just been removed from a refrigerator, had completely fogged up in the balmy, equatorial atmosphere. I conrinued rubbing the glass with a handkerchief, without any improvement. Note to self: When in the tropics, turn off the hotel room air conditioning and use a fan.

SBG produced about twenty-five species of bird for my day-list, including Java Myna, which, I learned later was in top contention for the most common bird in Singapore.

Link to: Annotated Singapore Bird List 2014 Callyn Yorke

The garden and grounds provided abundant forage and cover for birds. SBG consisted of about 150-acres of plantings, three lakes, and featured the world’s largest orchid collection. Unfortunately, during my wanderings in search of birds, I missed the latter exhibit.

The time change was catching up with me and I was soon exhausted. Around 10 am, I dozed off on a park bench and was rudely awakened by large drops of water hitting my face. A sudden, drenching thunderstorm – welcome back to the tropics! There was barely time to run for cover and protect the optics.

“Intrigued by remnants of British colonialism in the Malayan region, I took a taxi to the Raffles Hotel, built in 1822. Since I couldn’t afford the lowliest room there ($600 US), I settled for the least expensive item on the lunch menu ($30 US). Indeed, it was a memorable event – indulging in a bit of British colonial luxury.“

_______________________________________________________

June 6-13, 2014: Bunaken Island, North Sulawesi, Indonesia

“Hi Folks! After a couple of days of travel and one day entirely lost to the international date line, I have arrived in north Sulawesi. I’m staying on a small island called Bunaken, which apparently has been taken over by divers. The resort I’m at is called Living Colours, though it has mostly tanned white folks from Finland – the homeland of the owner.

Everyone here is very friendly. Last night we had a meet and greet at the bar. I learned that in the Finnish language there is no distinction between male and female; everyone is simply referred to as a “person.” Strange, yet very sociable folks, all of whom can speak excellent English. Since I am traveling alone, they feel obliged to look after me, rather like a distant visiting relative.“

Link to the Bunaken Dive Trip Report

For most visitors at the Living Colours resort on Bunaken Island, diving, eating, drinking, socializing and sleeping, were about the only options, and pretty much in that order. Soon I fell into the routine.

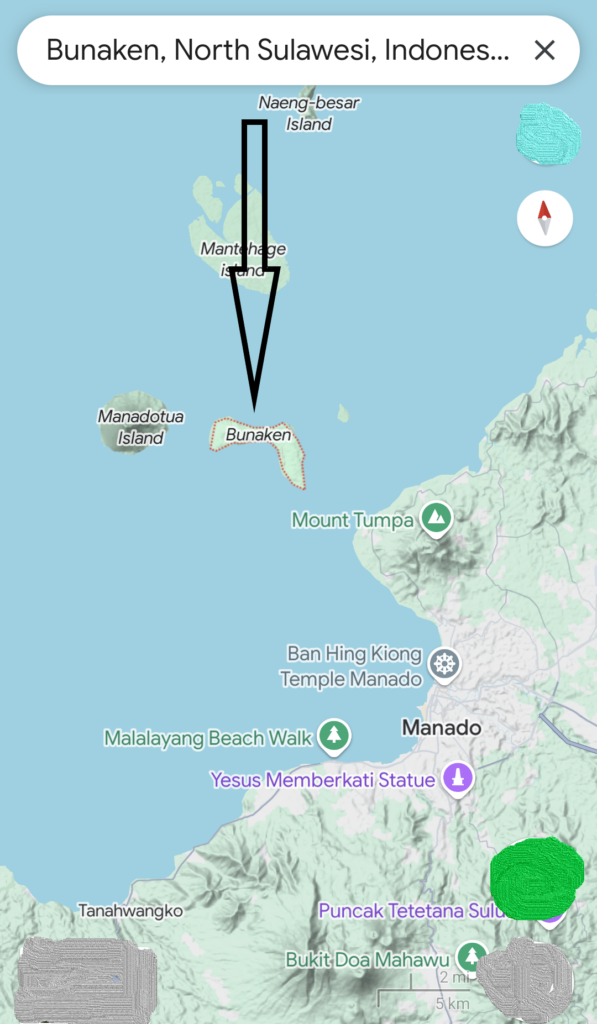

I took the first day off from diving and began exploring the island on foot. Bunaken didn’t look very big on the map, compared with the mainland of Sulawesi, about two miles offshore. However, having an area of about 1,740 acres, Bunaken was more than I could possibly survey in a few days of walking for a couple of hours in the morning and evenings.

I guessed that the area around the lodge and adjacent village (about fifty-acres), should contain, at one time or another, just about all the biodiversity (e.g. birdlife) the island had to offer. I had no way of actually knowing if that hypothesis was correct. However, after a few days of seeing the same bird species repeatedly, and no new ones added during the last two days, there was empirical support for my reasoning.

My first venture away from the resort ran into trouble with the neighbor’s dog. Seems I had wandered a little too far down the shore and into the dog’s territory. Like the local villagers, it had a surprised look on its face, as if to ask, “ Are you lost or something? Shouldn’t you be on a dive boat?” I took a detour and headed uphill, imagining I was being watched and followed.

Strange dogs in strange places. Unjustified paranoia? Perhaps. There was a convenient tree limb cutting that I fashioned into a walking stick/dog-deterrent. The emotional rescue crutch worked well. No sign of any dogs after that acquisition. I also took some comfort reflecting on the fact that Indonesian dogs were on the dinner menu and they probably knew it. In this part of the world, dogs usually kept a low profile around people, particularly the folks they recognized. A retreating foreigner, on the other hand, might be fair game.

Birdlife was scarce, shy and retiring; the most abundant species appeared to be noisy Slender-billed Crow and tiny, fast moving Garden Sunbird. Both of those species I had seen in Singapore and were part of an assemblage of widespread, opportunistic birds, biologist Jared Diamond referred to as “Supertramps.”

Jared Diamond (a UCLA distinguished professor and author of several national best sellers), along with other renowned biologists, e.g. Edward O. Wilson (a Harvard distinguished professor and Pulitzer prize-winning author), discovered that a number of geographical and biological variables were involved in predicting how many species would be on any given island at one time. Some of those variables were, a) the size of the island (larger islands tend to have more species than smaller islands, ignoring other topographical features), b) distance to the mainland (islands near a mainland had more species than distant islands), habitat quality (undisturbed forest supported more species than patchy forest), and finally, c) the dispersal potential of a given species (strong fliers generally get to islands more often than weak fliers).

For Bunaken Island, which is comparatively small in area yet close to the mainland (actually a very large, species-rich island called Sulawesi), we might reasonably predict that, all else being equal, there would be a relatively large diversity of birds. However, due to widespread habitat destruction (most of the original lowland rainforest had been removed and or heavily modified by agriculture), Bunaken’s bird species diversity would be correspondingly impoverished. Further, it is likely that there would be a high species and individual turnover rate on the island, as new arrivals replaced local extirpations. Theoretically, a dynamic balance is struck between local island extinctions and colonization from the mainland, though species-community composition may change fairly frequently.

By contrast, the neighboring volcanic island, Manado Tua (see above map), is slightly larger in area than Bunaken (2,570 vs. 1,740 acres) and has apparently retained much of the original rainforest. According to the island biogeography models proposed by MacArthur, Wilson and Diamond, Manado Tua should support a significantly richer avifauna than Bunaken. Yet, I am unaware of any systematic biological surveys conducted and/or published for Manado Tua Island. Curiously, Manado Tua also has a small population of Crested Macaque, which is a rare primate, endemic to northern Sulawesi (maybe they are good swimmers). Is anyone out there interested in a rather far fetched research project?

After about four days, I might have found half of the birds on the island, including a handful of vagabond birds such as Striated Heron, Collared Kingfisher, Sacred Kingfisher, Pied Imperial Pigeon (yellowish variant), Gray-cheeked Green Pigeon (a lifer for me), Emerald Dove, Moluccan Swiftlet (a lifer, separated from Uniform Swift by the former’s light rump), Glossy Swiftlet, White-vented Cuckoo Shrike (a lifer, and well-named), Hair-crested Drongo (a Sulawesi endemic form with white eyes; neither hair nor crest visible), Great-eared Nightjar (a lifer, identified by its distinctive repetitive calls), Pacific Swallow (a pair nesting under a resort bungalow) and a small flock of Javan Munia in the garden at Lorenzo village. Additionally, I noted about three or four vocalizations from birds I could not locate, possibly representing species not included on my Bunaken Island list. BTW, a “lifer” is a bird one has encountered for the first time. Welcome to the world of sport-birding, alias bird-watching.

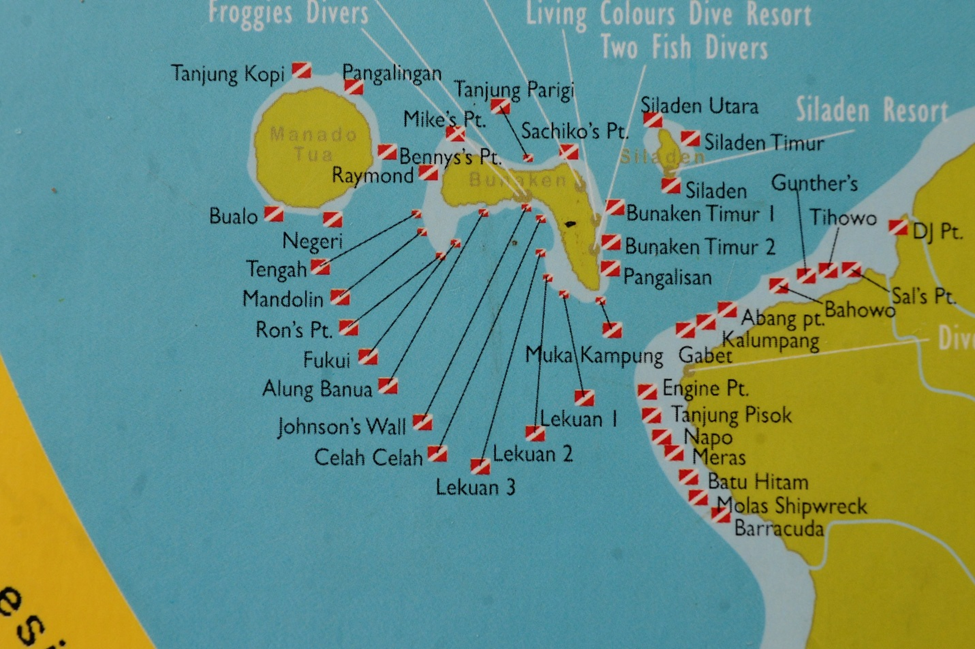

Bunaken and Manado Tua Island featured world-class, open water diving. Naturally, most of my time and effort on Bunaken was involved with that activity. At last, the heavy bag of dive gear I had been hauling half way around the world would be put to good use.

The Living Colours crew and dive masters were highly experienced and safety minded. Our dives routinely involved a buddy-check for functional gear prior to a backward roll off the gunnel. In a few more seconds, we released air from our buoyancy compensator vests and began the initial descent to about 25 feet, usually into a sandy clearing amongst huge coral growths. Swimming to the edge of a sheer cliff (the volcanic base of a sinking island), we dropped an additional 25 to 50 feet.

When looking downward from this depth, nearly everyone who was new to the area reported an immediate sensation of vertigo. In some places, despite vertical visibility of 100 feet or more, the bottom of the wall disappears into a dark blue abyss. In places, e.g. between Bunaken Island and Manado Tua, the ocean depth is about one mile. Often times, to maintain equilibrium, I had to focus on the wall rather than looking downward during a descent. My deepest dive was to 84 feet but usually we stayed within 60 feet of the surface. Nevertheless, my attention was frequently distracted by staring into the abyss, wondering what strange creatures lurked far below.

Some years ago, fisherman on Manado Tua Island caught a Coelacanth, a strange looking, lobe-finned fish. This was indeed an extraordinary discovery. The only other location for this “living fossil” known to science is in the Comoro Islands, off the east coast of South Africa. Coelacanths belong to a group of fishes known best by their fossil remains dating to around 120 million years before present. From observations of a small sample of living specimens, all of which died before their behavior could be studied in detail, we know that this peculiar fish lives at great depths, possibly in the 500-1200 foot range. Anatomically, it appears the Coelacanth uses its lobe-shaped fins (internal skeletal elements are homologous with the tetrapod humerus, radius and ulna) for swimming slowly and/or crawling in and out of caves and crevices.

Although much regarding its biology can be deduced from careful anatomical study, very little about the Coelacanth’s natural history is known to science, e g., its population size. Some biologists believe that due to its popularity among collectors (including museums) the Coelacanth may be endangered. Whether or not the Coelacanth at Manado Tua represents a different species or taxonomic lineage, remains an open question.

Following each dive, I logged the results of my observations. Though many of the life forms gradually became familiar to me, every dive site featured a bewildering array of new species. Most of the other divers were also interested in knowing what we saw; there were some fish identification cards onboard, which were initially helpful, though incomplete. Conveniently, the Living Colours resort library included a comprehensive and accurate photographic guide to reef fishes of Indonesia (Kuiter, R.H and T. Tonozuka 2004. Pictoral Guide to Indonesian Reef Fishes. P.T. Dive and Dives Press, Denpasar, Bali; 3 vols. 893 pp.). The latter reference was essential for the identification of fish I observed in Bunaken National Park.

By the end of my Bunaken diving tour, I had identified about 120 species of fish, representing only about 5% of the more than 2,000 species documented in Bunaken National Park. Additionally, I pored over hundreds of images that I obtained of marine invertebrates, including colorful Sponges (microscopic to gigantic), Cnidarians (e.g. sea anemone, branching, brain and soft corals; sea fan coral), Crustaceans (lobster, tiny reef crabs and candy-stripe shrimp), Molluscs (e.g. giant clam, conus, whelk, a beautiful white nudibranch and one secretive black octopus), Echinoderms (e.g. common blue sea star and aptly named, chocolate-chip sea star), Tunicates (several colonial forms, including one translucent blue species), Chondrichthyes (e.g. blue-spotted ray), and many Teleosts (bony fish) I failed to assign, in some cases to their correct taxonomic family.

I suspect that experienced ichthyologists may occasionally be unsure of a fish’s true identity. There has been widespread convergent evolution of body form and coloration among unrelated groups of reef fishes; identification of some species may be possible only with excellent quality photos and/or specimens. Included in this report are some of the underwater images I made while diving in Bunaken National Park. Any erroneous identifications are entirely my own (see preceding link to my Bunaken Dive Trip Report).

___________________________________________________

Northern Sulawesi June 7 – 21, 2014

My local birding guide, Christoph, whom I had corresponded with via email during the previous months, had been busy establishing our itinerary. He met me at the dock in Manado, with Kiki, his brother-in-law, whom agreed to be our driver.

Our first stop was an ATM, of which there are plenty in Manado and presumably elsewhere in Sulawesi. The conversion rate of $US was about 1: 11,000 Indonesian Rupiah. Since the biggest currency denomination is a 100K Rupiah note (roughly $10 US), it seemed I would be carrying around a backpack full of cash just to cover basic food and transportation. And there was another item of concern. Sulawesi ATM’s dispense a maximum daily withdrawal of only about $50 US. Fortunately, most hotels and large stores accept VISA, which becomes pretty much a necessity for transactions exceeding $100 US. More good news: Sulawesi is much less expensive than Singapore. For example, deluxe accommodation on the Sulawesi mainland can be obtained for $50-60 US per day. Food is ridiculously inexpensive; a full, three-course Indonesian-style meal costs less than $5 US. Public transportation is just pennies per mile. Long-term drivers will negotiate reasonable prices for their service. Car rental is available for about $60 US per day, but I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone lacking driving experience in the region.

Christoph was the go-to guy for just about all of our needs. In addition to making logistic arrangements for us, he demonstrated expertise in natural history and especially Ornithology. Christoph knew Latin binomials for all of the Sulawesi birds. He had received his field training while working for several international conservation organizations in Indonesia, including World Wildlife Fund. If that wasn’t enough, he and his brother in law, Kiki, provided a daily Bahasa Indonesia refresher course for me as we toured the countryside.

The Indonesian language is basically the same as Malay. Notable differences occur, however. Some shared words, e.g. Bisa and Boleh, carry quite different meanings (the former word means ‘poisonous’, as in snake venom, in Malay; and ‘can’, as in able to do something, in Bahasa Indonesia). Misuse of non-equivalent words between Malay and Indonesian must be common because I was seldom corrected for it. Or maybe Indonesians just expected me to blurt out a bunch of nonsense.

A few days with the staff at Living Colours, followed by much more conversation time with Christoph and Kiki, and I began speaking the Indo-Malay language again, which had been dormant in my memory for more than thirty years. Though semi-fluent in Malay by the time my three year Peace Corps Malaysia stint was over in 1980, I was now reduced to the level of an ambitious, bubbly, two-year old, grasping for words from somewhere, like remarks made by former president George W. Bush as he gazed at a map of the world, WOW! BRAZIL IS REALLY BIG ! Christoph, Kiki, and nearly every Indonesian I met on this trip, seemed delighted that I was stumbling comically through their lovely language, while attempting to put sophisticated ideas across such as, “It looks like rain again this evening.” Luckily, grammar for spoken Bahasa Indonesia is wonderfully simple. For example, verbs are all in one tense. A sentence in English such as, I am going to sleep now, translates in Bahasa simply to Saya tidur. No matter how I put the words together, Christoph and Kiki understood what I meant.

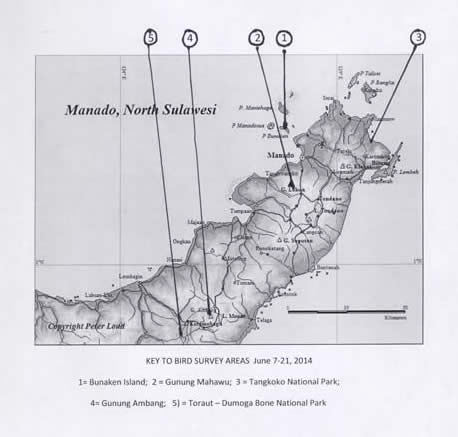

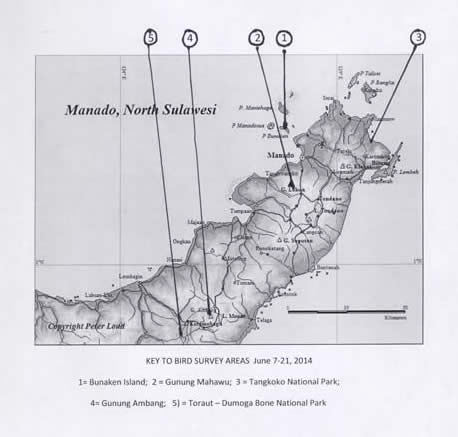

Northern Sulawesi Bird Trip Report Summary and Systematic Bird List

June 7 – 21, 2014 © Callyn Yorke

Weather: A full range of equatorial weather was observed, ranging from clear and warm afternoons (80F to 90F) to early morning and evening thundershowers (60F). Rainfall occasionally hampered our attempts to bird (e.g. Toraut and Gunung Mabawu) but was generally short in duration (i.e. < 1 hour). Humidity was usually high throughout the region (i.e. 80-95%). Ocean surface temperature averaged around 80F. June is usually considered the “Dry Season” in Northern Sulawesi, however global climate change has resulted in some deviations from this pattern, e.g. unexpected alternatiions of dry and wet spells.

Time: We generally began birding just after dawn (0600 hrs.) and, except for a few night-time excursions for owls, quit an hour before sunset (0630 hrs.). About 1.5 days were spent on roadways in transit.

Observers: Primarily Christoph Merung and I; also local park ranger-guides (e.g. Tangkoko and Tombon). I birded Bunaken Island alone.

Areas Covered:

Gunung Mabawu, including the Highland Resort – Gunung Lukon area of Tomohon, Sulawesi (GM: June 13-16, 2014): Christoph and I birded the lower and upper slopes of Gunung Mabawu (June 13: 1400-1600 hrs; June 14: 0600-0900 hrs.), including the rim of the crater of this inactive volcano (June 13 only). The slopes are covered by a mature lower-montane rainforest (photo), grading to smaller trees and weedy second growth near the rim. Most of the birdlife was found in the heavily wooded lower slope areas, where a paved road provided a convenient route for our walking surveys. Apparently, the Gunung Mabawu area is within a designated nature preserve; signs posted along the entrance road indicated that hunting and other disturbances were not permitted. The elevation of our surveys ranged between 2,000 and 3,000 ft above sea level. While staying at the nearby Highland Resort (HR), I birded their gardens and the adjacent hill forest below Gunung Lokon (an intermittently active volcano) in the morning and evening hours, weather permitting (June 14-15). Afternoon and early morning showers occurred frequently over the four-day period. Several Sulawesi endemics were found in this area, including, Greater Sulawesi Hanging Parrot, Yellow-billed Malkoa, Sulawesi Pygmy Woodpecker, Sulawesi Babbler, and Yellow-sided Flowerpecker.

Tangkoko National Park (TNP: June 16-19 June, 2014): Our base of operations for this area was the Tangkoko Ranger Home Stay, adjacent to Mama Roo’s Home Stay in Batu Putih village, bordering TNP (photo). The accomodations here were basic: a 10×10 ft. room with an attached bath. The bathroom sink and shower produced a dark brown liquid when initially turned on, grading to a tan-colored substance representing the normal running water supply for Batu Putih. The homestay fee (about $30) included three freshly prepared meals (e.g. steamed white rice, fish and vegetables) and drinking water (5-gallon bottles trucked in weekly). Our driver, Kiki and his brother-in-law, Christoph, stayed here without charge, except for their food, for which I was held accountable. The location was convenient, being only steps away from the entrance gate to TNP. We were soon assigned a female ranger guide named Ace (pronounced ‘ACHAY’), one of only a few women among some forty male rangers working in the park. Her fee was about $10 per day; the TNP fee was $20 per day, payable at the park entrance by all foreigners (Indonesians and guides enjoy free admission to the park).

We spent most of the day and part of the evening (June 17: 0530-0930 hrs.; 1100-1215 hrs.; 1430-1930 hrs.) in the park, hiking through the lowland hill forest bordering the shore. Sightings of birds were few and far between; those found were usually high in the canopy overhead and difficult to observe and photograph. Our guide, Ace, knew where to find the most popular endemic birds and wildlife (e.g.Green-backed Kingfisher, Knob-billed Hornbill, Crested Macaque and Spectral Tarsier), but didn’t seem to know much else about the natural history of the area. Luckily, Christoph was well-prepared and experienced in this region, and pointed out most of the birds, identifying them by their Latin binomials. Later, we teamed up with a friendly native named Yopi, who knew a great deal of local natural history, including latin names of plants used for medicine and where the most secretive bird species could be found, e.g. Ruddy Kingfisher.

Our visit to Tangkoko included a side trip by boat to a mangrove area (popular with visiting birders) adjacent to Kampung Kalinaung (KK), located about 5 miles north of Batu Putih (June 18: 1415 -1740 hrs.). Unfortunately, the boat’s captain decided to take us (Christoph, Ace and I) and two of his kids there at low tide. Not surprisingly we ran aground on a sandbar before reaching the mangrove (photo). After fifteen minutes of tugging, pushing and grunting by the captain (clearly dramatized for our sake), we abandoned the vessel and waded ashore, sloggging along the muddy edge of the mangrove as far as possible, which wasn’t more than sixty yards into a network of tidal sloughs in a mangrove forest. All of those waterways would have been easily navigable by our boat at medium to high tide.

Probably as a result of the unexpectedly limited incursion into the mangrove, we missed seeing one of its most remarkable inhabitants, the endemic Great-billed Kingfisher. This was perhaps the most regrettable dip of my Indonesian birding adventure. Adding financial insult to academic injury, the unapologetic captain refused to issue a partial refund (he was paid $60 in advance the evening prior to our trip) or return us free of charge to the location the following day at high tide. Needless to say, I left nothing in a jar labeled TIPS, that was fastened to our seating area at the bow of the boat.

Noteworthy birds found in the Tangkoko area and not found elsewhere during my visit to Sulawesi (excluding those species already named above), included, Pacific Reef Heron, White-bellied Sea Eagle, Ornate Lorikeet (endemic), Bay Coucal (endemic) Sulawesi Scops Owl (endemic), Purple-winged Roller (endemic), Rufous-backed Thrush (endemic), Finch-billed Myna (endemic) and Golden-bellied Gerygone.

Gunung Ambang (GA: June 19-20, 2014: 1530-1920 hrs.; 0730-0920 hrs.). After nearly an all-day drive from Tangkoko N.P., we arrived in the mid-afternoon in the village of Sinsingon, at the foot of GA. There we were met by Julius, a park ranger who invited us to stay in his home for the evening. This was an unofficial “Home Stay” and apparently the only accomodations Christoph could find for us in the area. We were treated with respect and warm hospitality, two large Indonesian meals (dinner that evening and breakfast the following morning), two sleeping rooms, and charged about $70 for all of it, including a strenuous though largely unproductive 4-hour birding tour on the north side of mountain, the evening of our arrival.

The following morning we drove through a mountain pass to the south side of GA, where an unpaved road cut through a well-developed lower-montane rainforest. Kiki let us out of the car at several places and proceeded ahead so that Christoph and I could walk a mile or so down the road, bird the surrounding forest, and be driven to the next spot. Many places along the road afforded eye-level views of birds in the forest canopy. Compared with Julius’ mountaineering bird tour the prior evening, where we stumbled back to our car in the dark, the mountain road from GA to Kotamobagu was refreshing. Much to our surprise and delight, the roadway through the forest produced some of the most exciting birding of our travels in Northern Sulawesi.

Birds of note found along the GA to Kotamobagu road included, Black Eagle, Brown Cuckoo-Dove, White-bellied Imperial Pigeon (endemic), Black-naped Fruit Dove, Caerulean Cuckoo-Shrike (endemic), Sulawesi Cicadabird (endemic), Sulawesi Drongo (endemic) White-breasted Wood Swallow, Fiery-browed Myna (endemic) and Scarlet Honeyeater.

Toraut, Dumoga Bone National Park (TOR: June 20, 2014: 1115-1730 hrs): Continuing our drive south from Gunung Ambang, we passed through Kotamabagu and arrived at the Toraut park headquarters at 1115 hrs., June 20. We were met by the park ranger-caretaker-guide, Jaimie, who showed us our rooms. Once an upscale World Wildlife Fund research facility for university staff and students, the place had fallen into serious disrepair over the past few years. My room ($30/night), though spacious, was infested by termites, mould and bedbugs. The shared lavatory was a tiny, tiled room with a squat-style toilet, a pale of water with a saucepan and a 3-ft. hose-bidet. There was a rusty shower head on the opposite wall aimed directly at the toilet. Hot water was unavailable. Intermittent rain continued through the afternoon and early evening, producing a welcome relief from the mid-day heat and humidity (65F to 85F; H 85-95%).

Fortunately, there were birds to be found in and around the facility. Jaimie showed us the roosting place of a Speckled Boobok among the rafters in an abandoned building next to the kitchen. At dusk a Blue-faced Rail appeared in the garden outside the dining area. Both of these species were Sulawesi endemics and new for our trip-list. The forest and open areas surrounding the facility also produced Black Kite, Green Imperial Pigeon, Blue-backed Parrot and Asian Palm Swift.

Tombon, Dumoga-Bone NP (TOM: June 21 2014: 0545 – 1100 hrs.). We had an early start from Toraut and drove in the dark directly to the Tombon park headquarters, arriving there at dawn. We were met by Max, the resident park ranger, who took us to the nearby Maleo nesting area. Although the endemic and endangered Maleo ranges widely in Northern and Central Sulawesi, Tombon was one of the only places we would be likely to see this peculiar species.

Max unlocked a gate next to a Maleo recovery information sign, and led us on a path through a lowland rainforest dominated by palms and hardwoods. A hot springs in this area provides the subterranean warmth sought by Maleos when excavating burrows for their eggs (the odd helmet-like growth on the Maleo’s head evidently functions as a thermometer). Although there were many older and some relatively recent excavation sites in a small clearing, we were unable to obtain more than a fleeting glimpse of an adult Maleo, despite more than three hours of searching and waiting patiently next to the nesting grounds. As a consolation prize, we observed Jaimie, one of the local researchers, excavate a fresh Maleo burrow and retrieve a single, large egg. The egg was quickly transported to a nearby pen and reburied inside for protection from predators (e.g. monitor lizards and local villagers). Next to the egg pen, a recently fledged Maleo chick awaited its release to the wild (photo). The Maleo recovery project, now in its 10th year, has hatched and released several hundred birds. The fate of the released birds is unknown. However, judging by the great number of Maleo nests in the area, the population appears to be relatively large and healthy.

During our search for the Maleo we encountered a few other birds of interest, including three more endemics: Sulawesi Black Pigeon, Ashy Woodpecker (see frontispiece) and Pale-blue Monarch. Other species new for our trip-list, included Blue-breasted Quail and close-up views of an immature male Blue-breasted Pitta, the only representative of its family we encountered during my tour of northern Sulawesi.

__________________________________________________________

SYSTEMATIC LIST OF BIRD SPECIES OBSERVED IN SULAWESI June 7 – 21, 2014

Callyn Yorke

SYSTEMATIC BIRD LIST : Taxonomic order and nomenclature largely follows Clements 6th edition (updated 2013): Avibase – Bird Checklist of the World – Sulawesi, by Dennis Lepage, 2014). Regional field guide used for identification and range: Coates, Brian J. and K. David Bishop. 1997. A Guide to the Birds of Wallacea. Dove Publications, Queensland, Australia. 535 pp. Sulawesi endemic species are in bold type. Estimated numbers of individuals observed are indicated following the scientific name.

GALLIFORMES

Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo) 1 (adult); 1 (fledgling raised in captivity); 1 24-hr. egg retrieved and reburied in an enclosure for protection; an adult Maleo was seen briefly running on the ground in the forest; another individual was seen by a researcher in the forested area. at least three birds were present in the forest surrounding the nesting grounds during our visit, TOM.

Orange-footed Scrubfowl (Megapodius reinwardt) 1 running away from us through the forest, TNP.

Blue-breasted Quail (Coturnix chinesis) 1 edge of agr. area. GA; 1 running through dense undergrowth in a forest clearing, TOM.

PELICANIFORMES

Great Egret (Ardea alba) 1 in rice paddy near Todano, Sinsingon, GA.

Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) 20 + paddy fields and roadside ditches near Todano, Sinsingon, GA.

Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) 120 ubiquitous in wet areas.

Javan Pond Heron (Ardeola speciosa) 15 paddy fields near Todano, GA.

Striated Heron (Butorides striatus) 1 edge of mangrove, TNP.

ACCIPITRIFORMES

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) 1 adult. circling above the shore near mangrove estuary, TNP.

Black Eagle (Ictinaetus malayensis) 1 soaring high above the forest, GA.

Eastern Marsh Harrier (Circus spilonotus) flying low over a flooded field near Todano, GA.

Black Kite (Milvus migrans) 1 flying over open agricultural fields, GA; 2 perched in tree at dusk, TOR.

Brahminy Kite (Heliastur indus) 1 flying over shore and mangrove, TNP.

White-bellied Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) 4 flying over shore and beach scrub; a pair in a tree on offshore islet, TNP.

GRUIFORMES

Barred Rail (Gallirallus torquatus) 5 common on roadways and trails at GM and GA (photo).

BLUE-FACED RAIL (Gymnocrex rosenbergii) 1 observed at close range for several minutes foraging on ground in the garden, TOR.

COLUMBIFORMES

Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) ubiquitous in towns.

Spotted Dove (Streptopelia chinensis) ubiquitous in towns and villages.

Slender-billed Cuckoo-Dove (Macropygia amboinensis) 8 feeding on medium-sized yellow fruits of emergent next to the Highland Resort, GM; 3 in forest canopy, GA.

Emerald Dove (Chalcophaps indica) 2 BI; 1 TNP.

Gray-cheeked Pigeon (Treron griseicauda) 5 perched together in canopy of tall tree near the main village, BI.

Black-naped Fruit Dove (Ptilinopus melanospilus) 3 foraging in the canopy of a large fruiting tree, GA.

White-bellied Imperial Pigeon (Ducula forsteni) 2 together in the canopy of a large emergent tree, GA.

Green Imperial Pigeon (Ducula aenea) 4 together in canopy of emergent tree, TNP.

Pied Imperial Pigeon (Ducula bicolor) 3 flying over mangrove, BI; 25 a cohesive flock in trees and flying around small offshore island in the late afternoon, TNP.

CUCULIFORMES

Plaintive Cuckoo (Cacomantis merulinus) 5 heard calling loudly and repeatedly in forested areas, GM, GA, TNP.

Yellow-billed Malkoa (Phaenicophaeus calyorhynchus) 2 GM (photo); 1 TNP; 2 GA.

Bay Coucal (Centropus celebensis) 1 flying between bamboo and streamside thickets; secretive, Batu Putih, TNP.

Lesser Coucal (Centropus bengalensis) 1 in shrubs at the edge of an agricultural field, GM; 1 calls, weedy area around Batu Putih village, TNP.

STRIGIFORMES

Sulawesi Scops Owl (Otus manadensis) 1 in a daytime roost of giant bamboo on the grounds of a new Batu Putih guest house, TNP.

Cinnabar Boobok (Ninox ios) 1 calls only (GM), lower montane forest edge, Sinsingon, GA.

Speckled Boobok (Ninox punctulata) 1 in daytime roost in rafters inside an abandoned building adjacent to the kitchen, TOR (photo).

CAPRIMULGIFORMES

Great-eared Nightjar (Lyncornis macrotis) calling repeatedly from a clump of giant bamboo next to the dining area, BI; calls, Batu Putih, TNP.

APODIFORMES

Glossy Swiftlet (Collocalia esculenta) ubiquitous except for BI, where replaced by Halmahera Swiftlet; usually flying low over open areas.

Halmahera Swiftlet (Aerodramus infuscatus) 8: visible characteristics (using photos): blackish-brown above with distinctly lighter (gray, not white) rump. In pairs and loose flocks, flying fast, back and forth above second growth and tree-tops and tall shrubs, never less than 10 feet above the ground. Seen daily above around the Living Colours resort, Bunaken Island, BI.

Uniform Swiftlet (Aerodromus vanikorensis ) ubiquitous, except BI; usually in loose flocks of 3-5 individuals, flying high above the forest and clearings; lower after rains.

Swift (Apus sp. c.f. pacificus/nipalensis) 2 a relatively large species with a light rump; flying very high above towns and villages in the highlands, GM.

Asian Palm Swift (Cypsiurus balasiensis) 2 flying 20-100 ft. above ground, back and forth over bridge and river, TOR.

Gray-rumped Treeswift (Hemiprocne longipennis) ubiquitous at the edge of forested areas.

CORACIIFORMES

Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) 1 flying upstream, Batu Putih, TNP.

Ruddy Kingfisher (Halcyon coromanda) 1 well-concealed among streamside shrubs, Batu Putih, TNP.

Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris) 4 vocal, ubiquitous; edge of mangrove and second-growth, BI.

Sacred Kingfisher (Todiramphus sanctus) 2 perched in tall trees in open areas, BI; TNP.

Green-backed Kingfisher (Actenoides monachus) 1 lower strata of forest, TNP; 1 TOM.

Purple-winged Roller (Coracias temminckii) 1 active in middle level of forest along trail, TNP.

Knobbed Hornbill (Aceros cassidix) 2 m,f; female, difficult to see, masoned into nest cavity about 30 ft. above the ground in a mature fig tree in primary rainforest; male foraging in subcanopy nearby, TNP.

PICIFORMES

Sulawesi Woodpecker (Dedrocopus temminckii) 2 m,f pair working up trunks of separate hardwood trees at the edge of the forest, GM; size,morphology and behavior suggested a closer affinity with Picoides than Dedrocopus.

Ashy Woodpecker (Mulleripicus fulvus) 1 f; a large, powerfully-built woodpecker; climbing slowly and silently up the trunk of small tree at the edge of a forest clearing, TOM (photo).

PSITTACIFORMES

Golden- mantled Racquet-tail (Prioniturus platurus) unclear views; calls (CM) flying over the canopy of a primary rainforest,TNP.

Azure-rumped Parrot (Tanygnathus sumatranus) 2-5; vocal and active at dusk in trees outside dining area, TOR.

Sulawesi Hanging Parrot (Loriculus stigmatus) 2 climbing in subcanopy of fruiting tree at the edge of the forest, GM (photo).

PASSERIFORMES

Red-bellied Pitta (Pitta erythrogaster) 1 immature male; foraging in leaf litter beneath trees, TOM (photo).

Sulawesi Myzomela (Myzomela chloroptera) 1 m foraging in middle to upper levels of roadside trees, GA.

Golden-bellied Gerygone (Gerygone sulphurea) 5 foraging in Kmpg. Kalinaung mangrove at the edge of a slough, TNP.

White-breasted Woodswallow (Artamus leucorhynchus) 2 sallying from an exposed perch, GA.

Cerulean Cuckoo-shrike (Coracina temminckii) 2 foraging busily, together canopy of fruiting tree, GA.

White-rumped Cuckoo-shrike (Coracina leucopygia) 2 sallying from subcanopy of tall trees at the edge of a clearing, BI.

Sulawesi Cicadabird (Edolisoma moria) 4 together in subcanopy and middle layer of forest; sallying from exposed perch, GA.

Black-naped Oriole (Oriolus chinensis) ubiquitous around villages; montane forest edge and wooded areas with second-growth.

Hair-crested Drongo (Dicrurus hottentotus) 2 wooded areas, BI; 1 GA.

Sulawesi Drongo (Dicrurus montanus) 1 subcanopy of primary rainforest, TNP.

Pale-blue Monarch (Hypothymis puella) 1 sallying from the middle-level of a wooded area, TOM.

Slender-billed Crow (Corvus enca) 5 vocal, active in mangrove, BI; 2 TNP; 2 GA.

Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) 2 flying low over clearing near shore, TNP; nesting under eaves of isolated building in agr. field, GM.

Pacific Swallow (Hirundo tahitica) 4 adults with young in nest underneath a bungalow; flying low over shore, BI; 2 flying low in clearings,TNP.

Citrine Canary-Flycatcher (Culicicapa helianthea) 1 active in subcanopy of mid-elevation forest, GM.

Sooty-headed Bulbul (Pycnonotus aurigaster) ubiquitous in village gardens and agricultural areas, GM.

Mountain Tailorbird (Phyllergates cucullatus) 1 active in lower levels of roadside forest, GM.

Golden-headed Cisticola (Cisticola exilis) 1 shrubby second-growth and tall grass on roadside, GM.

Mountain White-eye (Zosterops montanus) 3 active in subcanopy of high elevation forest, GM.

Sulawesi White-eye (Zosterops consobrinorum) 1 active at upper middle level of dense, low elevation forest, GM.

Sulawesi Babbler (Pellorneum celebense) 1 vocal and active in lower level of dense, low-elevation forest, GM.

Rusty-backed Thrush (Geocichla erythronota) 1 vocal and active in streamside vegetation, Batu Putih, TNP.

Asian Glossy Starling (Aplonis panayensis) 8 in canopy of tallest trees; vocal flock staying together, BI

Fiery-browed Myna (Enodes erythrophris) 3 together, feeding on fruits of tall forest tree, GA. .

Finch-billed Myna (Scissirostrum dubium) 20 vocal and active in late-afternoon in tall, dead tree with cavities, TNP.

Yellow-sided Flowerpecker (Dicaeum aureolimbatum) 2 active in subcanopy of high elevation forest, GM (photo).

Garden Sunbird (Cynniris jugularis) 10 m,f; vocal, active in gardens and second-growth, BI; 2 in garden, Highland Resort, GM.

Crimson Sunbird (Aethopyga cervinus) 1 male active in montane forest and grassy area at high elevation, GM.

Eurasian Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) ubiquitous in villages and towns.

Black-faced Munia (Lonchura molucca) 4 foraging together in grassy area and garden, BI.

Java Sparrow (Lonchura oryzivora) 2 garden and lawn, BI.

____________________________________________________________