Mekong Delta: Tràm Chim National Park, Tam Nông Tinh Đồng Tháp; Tân Thành, Gò Công Đông, Việt Nam January 3-9, 2024 Callyn Yorke

Scroll down for the Annotated Bird List

Introduction

It took a few million years of tectonic contortions in the Tibetan Himalayas to give birth to the the twin river systems currently flowing into to the East Sea: The Mekong and Red River. These legendary waterways now empty into deltas near the southern and northern Vietnamese borders, respectively. The vast Mekong Delta, probably for the previous 1.5 million years, has been one of the most significant wintering grounds for migratory waterbirds in Southeast Asia.

Based on recent reports, I anticipated that the Mekong Delta would be an exciting and productive place for observing a diverse assemblage of resident and migratory birds. That was indeed the case at Tràm Chim and Tân Thành.

The latter location is a critically important wintering ground for migratory shorebirds, including the world’s rarest and most endangered shorebird, Spoon-billed Sandpiper, which was a life-bird for me, as well as for a small group of visiting birders who, led by professional Vietnamese guides, dropped in to search for this bird on the morning of January 9, 2024.

No less important as a waterbird refuge, is the 7,500 hectare Tràm Chim National Park, where the endangered Eastern Sarus Crane occurred historically, possibly in double-digit numbers. Nowadays, a few of these impressive birds may occasionally overwinter in the Mekong Delta, ‘Plain of Reeds,’ when its preferred food items, i.e., roots and tubers, are available. Ecological restoration projects are underway in Tràm Chim and there is a renewed vision that the Sarus Crane will return to the area in the near future.

Thanks to the Vietnam Forestry Department and several independent Vietnamese conservation biologists, e.g. Professor Nguyễn Hoài Bảo, in collaboration with multinational organizations, e.g. International Crane Foundation (ICF), BirdLife International (BLI), and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), there are educational and conservation programs being planned to raise public awareness of this ecologically significant area.

Ecotourism is an important step in that direction. One section of the park, i.e. Area #1, adjacent to the Wildbird Tràm Chim Hotel, is readily accessible to visitors. I spent several days there (January 3-8, 2024) observing and photographing resident and migratory birds, some of which, e.g. Asian Openbill, Oriental Darter, Bronze-winged Jacana and Black-capped Kingfisher, are uncommon breeding birds elsewhere in Việt Nam.

Following my stay at Tràm Chim National Park, Đồng Tháp, I visited the coastline of Tân Thành, Gò Công Đông (January 8-9, 2024). With me, Hồ Phú Quý (‘Quý‘), an apprentice bird guide employed by Wildbird Tràm Chim Hotel. That journey, though comparatively brief, was one of my most memorable birding experiences in Southeast Asia. Tân Thành had by far the greatest number and variety of wintering shorebirds that I had seen in Việt Nam.

Survey Areas, Methods and Materials

Tràm Chim National Park, Tam Nông Tinh Đồng Tháp (January 3-8, 2024)

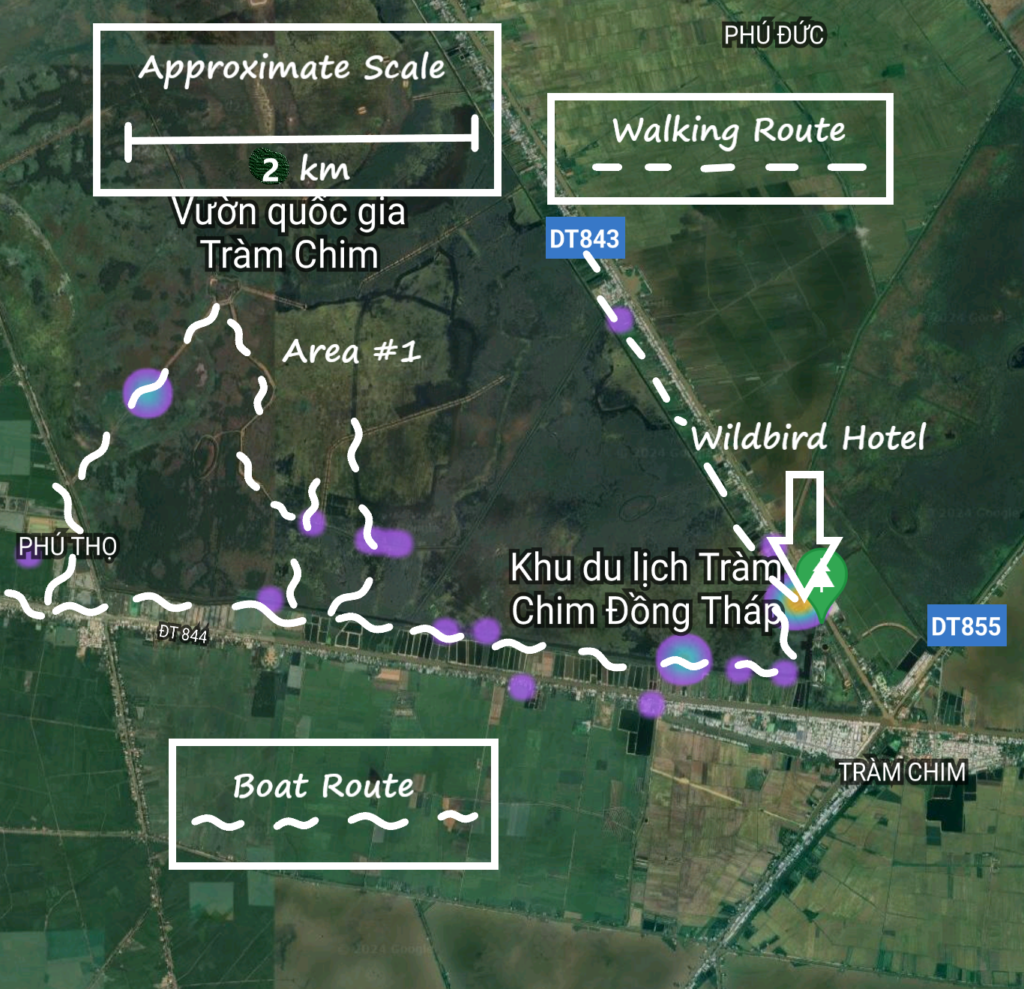

The Mekong Delta journey began in District 1, Saigon, where I booked a one-way taxi to Tràm Chim (3.5 hrs. $75 USD). My home base was the Wildbird Tràm Chim Hotel, a comfortable, fully renovated facility (3-Star, $30 USD), featuring a gourmet restaurant and lovely staff. There, I made multiple bird surveys on foot and two by boat (see the following satellite map). Most of the bird surveys were with the young and enthusiastic, Hồ Phú Quý (‘Quý‘). The hotel owner, Nguyễn Hoài Bảo (‘Bảo’) and his wife were gracious hosts during my visit, arranging boat tours of Tràm Chim National Park and logistics for a subsequent trip to Tân Thành and return to Saigon. Additionally, Bảo generously offered his considerable expertise as a bird guide in Tràm Chim and Tân Thành.

Daily bird surveys were made while stationary at the hotel (e.g. from the restaurant) and walking the canal embankments originating at the lodge and extending northward for a distance of about 2 km. Two motorboat surveys were made of Area #1 in Tràm Chim National Park (January 4 &7, 2024), visually covering an area totaling about 120 hectares (see accompanying satellite map).

For all surveys, I used a Zeiss 10 x 42 binocular and hand-held Nikon D3X camera fitted with a Nikon PF 500mm IF, VR lens. A Google Pixel 3X cell phone camera was used for general scenery and points of interest; images included GPS metadata from which survey routes could later be mapped. A pocket notebook was used for data entry and recopied into a loose leaf binder format each evening. My field notes and digital images formed the basis for this report.

Weather during my visit was typical during the winter dry season – overall, quite pleasant – with early morning clouds and haze, turning to mostly clear skies; ambient air temperatures ranged from 19°C to 32°C. NNE winds were light (2 – 10 kph).

Habitats surveyed, included patches of reforested, exotic Paperbark Cajeput (Melaleuca cajuputi) with scattered stands of tall Eucalyptus spp.. Wooded areas occurred along pathways and canals near the hotel and in Tràm Chim National Park. Bordering dredged sloughs, canals and backwaters, were large fields of open grassland and marsh, collectively part of the seasonally flooded Plain of Reeds, a significant ecological zone in the upper Mekong Delta.

Waterbirds were conspicuous and abundant in Tram Chim National Park, especially along the main, east-west slough. Mixed species flocks of birds were easily seen and photographed in marginal lotus ponds and on peat mudflats. Around the hotel, neighboring ponds, gardens and second-growth with admixtures of native and exotic shrubs and trees, provided additional microhabitats frequented by resident and migratory land birds. Considering that virtually all of the Tram Chim habitats have been drastically modified as a result of at least 2,000 years of continuous human occupation, it is remarkable that this area supports such a large variety of birds and other wildlife.

The last remnants of native lowland Dipterocarp forest in the upper Mekong Delta probably disappeared around 150 years ago, when replaced by small settlements and shifting, slash and burn agriculture. During the American-Vietnamese war (1965-1975) there was further habitat modification and ecological degradation, including the draining of wetlands and applications of broad-spectrum herbicides (i.e., ‘Agent Orange’).

Very little is known of the original wildlife inhabitants of this area. Only in recent years have systematic biotic surveys been conducted in the Mekong Delta. Preliminary results indicate the area still supports viable populations of breeding birds and other wildlife, well deserving of current preservation initiatives.

Birds were visible throughout the day in the wetlands and adjacent areas, with peak activity from 0700-1000 hrs. Quý, the Wildbird Hotel’s sharp-eyed birder and naturalist, was very helpful. Together, we managed to identify the majority of the birds encountered, either by sight or sound, including at least two species that were new to Quý, e.g. the newly minted, Black-eared Kite (Milvus lineatus) – a tentative species split from its northern counterpart, Black Kite (Milvus migrans) and a skulking, easily overlooked, Radde’s Warbler (Phylloscopus schwarzi). Quý updated his eBird account records with a cellphone during our surveys, while I made old-school shorthand entries in a pocket notebook.

Tân Thành, Gò Công Đông

Bảo and his wife had arranged a car and driver for transporting Quý and I from the Wildbird Hotel to Tân Thành, a four-hour journey. They recommended Hotel A Châu, a basic (2- Star) hotel on the main street (Thành Nhung) in Tân Thành. The hotel was in a fairly quiet, convenient location with clean rooms and private baths ($8.30 USD).

Soon after checking into the hotel in the early afternoon of January 8, we drove along the coastal roadways in search of appropriate habitat for birds, i.e. shoreline and mudflats. Strong onshore winds and a high tide, appeared to have temporarily squelched our plan to search for shorebirds, particularly the grand prize, Spoon-billed Sandpiper. However, that premature assessment, thankfully, turned out to be misguided. We merely needed a route to the distant sandbar peninsula. There, we would find hundreds of shorebirds gathered at high tide.

As anyone fond of birds would surely expect, most of our birding effort in Tân Thành was directed toward finding the Spoon-billed Sandpiper, a rare and critically endangered, migratory shorebird, breeding in northeastern Siberia and the Chukotsky Peninsula. The Spoon-billed Sandpiper has been suffering a steady decline in its population during the past two decades. Current estimates are that only about 500 mature individuals remain on the planet (Nguyen ,H. B, T.T. Le, et. al., 2023. Wader Study 130 (1)).

The recent discovery and photo-documented report by Vietnamese birder, Thàn Bùi Trung (‘Toby’), indicated at least three ‘spoonies’ (including one that was leg-banded in Siberia) were overwintering in Tân Thành. That exciting new discovery definitely turned up the probability dial for Quý and I finding the bird.

Since Quý and I were unfamiliar with Tân Thành, we relied on fragmentary maps, notes and casual remarks made by others who had visited recently and knew something about the habits and location of Spoon-billed Sandpipers. But specific directions for finding this special little peep were largely unavailable to us. We would be looking for the proverbial needle – in a mudflat.

Quý and I were on our own until the following morning, when Bảo and a visiting couple from Los Angeles would be arriving in Tân Thành. We had been invited to tag along with them. I was nonetheless confident that beforehand, with persistence and a bit of luck, we could find a Spoon-billed Sandpiper on our own. That goal was honorably lofty, like waltzing up to the summit of Everest without a guide and supplemental oxygen.

Everything would more or less work out favorably. At least my camera had captured a spoonie during our first afternoon in Tân Thành. Thus, it seemed quite possible that visiting birders without a professional guide, could find a Spoon-billed Sandpiper. But, just like us, I’m pretty sure they could use whatever local help might be available.

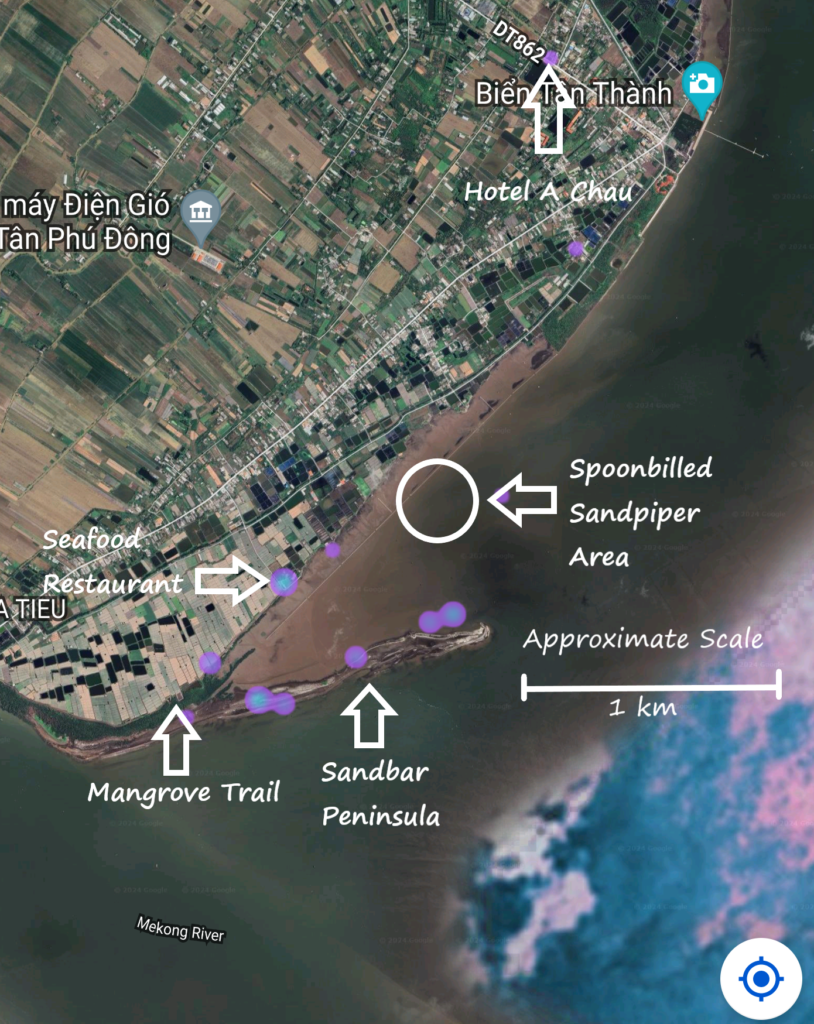

This report, if reviewed carefully, includes useful information for those wishing to observe a Spoon-billed Sandpiper. The satellite map and accompanying text aims to give birders a reasonably good idea of how and where to search for spoonies in Tân Thành.

It should be emphasized that this critically endangered shorebird and other migratory shorebirds, whether listed as endangered, threatened, vulnerable or not, are officially protected under Vietnamese and International laws. A reasonable effort must be made to insure that when viewing these birds there is minimal disturbance to them.

Aside from the main shoreline attractions, there were few land bird species to see in Tân Thành. Natural resources for foraging, shelter and nesting were scarce. Whatever birds could find for themselves was largely incidental to human activities. Usable habitat for land birds in Tân Thành was confined to small gardens, farms, orchards and patches of coastal scrub. Common Myna, Yellow-vented Bulbul, Common Tailorbird, Barn Swallow and Eurasian Tree Sparrow, predominated in those places. All of the aforementioned species are abundant, widespread and familiar commensals of humans. However, there was one bird species in the Tân Thành land bird assemblage of particular ecological interest to me: Germain’s Swiftlet. It was easily the most abundant species in the area, and for an obvious reason.

Swarms of hundreds of house-farmed Germain’s Swiftlet circled the town from dawn to dusk. These birds are essentially the open sky analogs of free-range chickens. Their domiciles are rather odd looking, multi-level buildings, unfurnished and without windows, having instead, rows of holes bored into exterior walls, like portals on a ship. Obligingly, the swiftlets prefer the cozy convenience of their modern homes, where they are sheltered from a suite of natural calamities, such as inclement weather and nest predation. Well, actually the latter problem still occurs for them; now as a controlled nest harvest by their landlords. Their specialized diet of aerial arthropods (primarily dipterans), naturally means the birds must do their own grocery shopping. And, just incase they become lost in a nearly constant and wide-ranging search for food, they can presumably home-in on recordings of their excited vocalizations played at maximum volume on loudspeakers throughout the day.

Inside a darkened swiftlet home, I imagine that the delicate little saliva nests are guarded with great care and concern. At current market rates, a 100g package of edible swiftlet nests sells for $100 USD (photo). Germain’s Swiftlet, and a few of their relatives elsewhere in Southeast Asia, gram for gram, are among the most highly valued birds in the world. That much is certain. And so is the probability that this lucrative aviculture business will continue to expand in Việt Nam.

Economic prosperity, however, may come with unexpected environmental costs. For example, during our brief visit, it was clear that other ecologically competitive swift species, recently fairly common and widespread in Việt Nam, were conspicuously absent from the skies above Tân Thành. The same tentative conclusion was reached following our coastal bird survey of Việt Nam a few months earlier. A noticeable decline in diversity of swifts is becoming an alarmingly widespread occurrence, particularly in the coastal lowlands of Việt Nam. Comparative field studies are urgently needed to assess the impact of swiftlet farming on natural communities of aerial-foraging birds. This type of scientific investigation, especially when involving students and faculty from Việt Nam universities, should coincide well with the objectives of the Việt Nam Biodiversity Action Plan (1993).

Realistically however, such study proposals are likely to be met with underwhelming enthusiasm. Globally speaking, economic progress usually defeats all other competing agendas, including wildlife conservation initiatives. Local communities will ultimately need to agree on how this popular type of aviculture can be environmentally managed for long-term sustainability.

Initial exploration of the Tân Thành sandbar peninsula and outer shore, 8 January, 2024

Shortly after checking into the hotel in Tân Thành on January 8, 2024, we ventured out toward the shoreline. I retained a vague mental image of the partial satellite map of Tân Thành that my friend Hai-Dang had provided from his recent, successful birding trip, guided by Thàn Bùi Trung (‘Toby’). Even with that relevant information, I was still unsure where the best shoreline access point was. Turning off the main street near the public beach, we went northward instead of southward, then spent the next half-hour or so, motoring back and forth on a narrow lane paralleling the beach, mangrove, aquaculture ponds and homesteads. Eventually, we ended up at the ‘correct’ location, Thu Hủơng Restaurant, a shoreline seafood restaurant about 2km south of Thành Nhung St.. Good timing. We were all ready for some spicy, freshly grilled garlic shrimp.

Quý made inquiries with locals at the restaurant and learned that there was access to the outer shore at high tide, about 1km southward through an adjoining series of melon farms, bordering the mangrove (see preceding satellite map). The winds of fortune had shifted in a favorable direction.

One of the more informative locals, a gleeful, slightly chubby Vietnamese chap, who had been darting glances at us while he and his buddies engaged in a beer-drinking social, got up, reached into a plastic bucket of ice and pulled out a can of Tiger Beer as a friendly offering. He had evidently been present to Quy’s conversation about finding a way to the outer sandbar. He said something in Vietnamese to Quý, who turned to me with the translation. This very kind Vietnamese fellow was offering us the use of his motorbike. When asked, “How much? “Không có gì“, was the young man’s reply. No payment was necessary. He indicated that he wanted only for us to have a good time. Cheers to that!

This was yet another of many examples why I have become very fond of Việt Nam over the years. Sure, Vietnamese people can sometimes sneeze loud enough to awaken the dead and habitually drive like they may soon join them. Every civilization has its quirks, some unpleasant, some delightful. In Việt Nam, forgiveness and spontaneous acts of kindness are commonplace – truly exceptional and beautiful aspects of their culture. And as far as visiting birders in Việt Nam are concerned, they can rest assured Vietnamese people will see that all needs are met.

Our tandem motorbike ride began on fairly straight, flat roads that abruptly merged with a progressively narrower ditch between two melon farms. Quý handled the 100cc machine like a motocross champion and we soon arrived safely and still upright, at the edge of a berm covered with a black plastic tarp. Temporarily abandoning the borrowed motorbike in a sprouting melon patch, we removed our footwear and waded through a short mangrove inlet leading to a sandbar peninsula.

This lengthy, narrow peninsula, at an average elevation of about 0.5m above sea level, was the only walkable ground at high tide. It consisted of compacted alluvial deposits, straight from one of the multiple mouths of the dendritic Mekong River, or as the Vietnamese call it, Sông Cửu Long – “River of Nine Dragons.”

Proceeding northeast on the peninsula brought us into view of the sediment laden waters of the East Sea. The outer shore, strewn with mollusk shell fragments, absorbed a heavy pounding from the relentless onslaught of muddy breakers. To the left of the sandbar peninsula, mudflats merged with regenerating mangrove (Avicennia alba), presently inundated. About 100m seaward from dry land, a 2m high concrete-block breakwater faced a row of aquaculture ponds and homesteads, including our lunch spot at the seafood restaurant. This sturdy wall was doubtless built to protect developments along the inner shoreline, especially during the southwest monsoon (May-October), with the highest river levels and tides of the year.

While on the southwesterly section of the sandbar peninsula at high-tide, we encountered Little Egret, Chinese Pond Heron and Striated Heron. There were also widely separated flocks of long-legged shorebirds, e.g. Eurasian Curlew, Common Greenshank and Bar-tailed Godwit. Many of the birds were standing motionless in the shallows; some were busily preening while awaiting the changing tide.

Continuing in a northeasterly direction, about 300m from where we began walking on the peninsula, were impressive numbers of small to medium-sized shorebirds, e.g. Lesser Sandplover, Greater Sandplover, Black-bellied Plover, Curlew Sandpiper, Terek Sandpiper and Great Knot. These mixed species flocks of biblical proportions, formed the majority of the high-tide refugees. A few of them flushed as we approached. Most remained grounded, nervously shuffling to sparse vegetative cover and concealing themselves behind low berms. We allowed the birds their space and observed them from distances of 50-150m. These overwintering birds were probably partially habituated to human presence, since this area during a low-tide attracted local clammers and fishermen. Further still, on the wave-battered outer shore, stood a mixed species flock of terns. That grouping included Gull-billed Tern, Greater-Crested Tern and Caspian Tern. Apart from them was a lone, small gull (any gull seen in southern Việt Nam is noteworthy), later identified from my digital camera images as Black-headed Gull.

In the northeast section of the peninsula, near the end of our high-tide excursion, Quý noticed that locals were setting up bird nets between long poles. Quý chatted with these folks the following day as I was removing a live Whiskered Tern from a net, and reported that they resented having to compete with birds for mollusks and other harvestable creatures. The 3m tall mist nets were believed to be effective bird deterrents. Unfortunately, birds (and bats) were left in the nets to suffer and expire, as were the crucified victims along Roman roads, serving as a grim warning to passersby. A sad and sobering sight, reminiscent of the widespread poaching Lê Quý Minh and I had witnessed during our Autumn 2023 Việt Nam Coastal Bird Survey.

Documenting the high-tide shorebirds of Tân Thành suddenly seemed a matter of urgency. I fired off a rapid series of telephoto images of these spectacularly massive flocks, which contained too many birds to count for spot-on species estimates. Additionally, some of the birds shifting within the flocks could not be seen clearly enough for positive identification.

Subsequently, when the camera images were examined closely on a laptop monitor, it was clear that my initial estimate of a 200-300 plovers and sandpipers was too low. Taken together, these multi-species flocks conservatively numbered 1,000 to 1,200 birds. Furthermore, bird species that were too distant for identification during our survey, e.g. Red Knot, Spoon-billed Sandpiper, Black-headed Gull, and Great-crested Tern, were fairly easily found and specifically assigned using the enlarged digital images.

………………………………………………….

Spoon-billed Sandpiper Safari, 9 January 2024

Early the following morning of January 9, 2024, Quý and I awaited the arrival of Bảo and his two visitors from California, Patrick and Daniela. There was time only for a brief meet and greet before setting out to find a Spoon-billed Sandpiper. We were at our designated rendezvous, the ‘seafood restaurant,‘ which, in honor of Tân Thành‘s famous part-time resident, perhaps could be renamed, the “Lovin’ Spoonbill Cafe.”

Bảo, Patrick and Daniela were already pacing around barefooted. A few minutes later, another carload of visiting birders arrived at the restaurant, which had not yet opened for business. When everyone was ready with their gear, we began walking single file toward the mudflat crossing point, about 200m north of the restaurant.

The only walkable path to the crossing point was through muddy piles of trash. The uneven pathway included fish nets, light construction debris, plastic water bottles, chunks of polystyrene, coconut shells, clam shell fragments and various small, unidentified objects, some of which could be sharply felt underfoot. I supposed that only the guides knew exactly what a big mess we were getting ourselves into. Holding one objective firmly in mind, we marched on with silent resolve.

The second segment of the triathlon would have us slogging through knee-deep mud. The reason for jettisoning footwear at the restaurant needed no further explanation. In some spots the mud stubbornly refused to release its grip. Next, there would be required, an ascent onto a makeshift scaffolding, bound by a segmented series of single, horizontal rails, slippery as snot, and elevated about 1m above a muddy channel. If that wasn’t enough of a challenge, this 100m Flying Wallenda death walk, faced directly into a blinding glare from the rising sun. It suddenly dawned on me – like Stevie Wonder arriving late for a beach party – my sunglasses and hat had been left at the restaurant.

I made it as far as the junction of deep mud and the Wallenda pole-walk. This wasn’t looking good. Others stepped around me, bravely climbing onto the slick wooden rail with their spotting scopes, tripods, binoculars and cameras, balancing precariously, carefully placing one muddy foot in front of the other. There was no way I would attempt that stunt with my camera gear and binocular awkwardly dangling from my neck. In fact, I had not yet downloaded my digital images from the previous day and could clearly visualize a faceplant in the mud, losing everything, including my dignity.

I signaled Quý that I was returning to the relative safety of the rubbish path. Quý, my faithful birding companion, surefooted as a mudskipper, agreed with the decision and gave me a hand for rotating to a reversed heading. Meanwhile, the others successfully negotiated the mudflat crossing, climbed over a breakwater wall and proceeded onto comparatively solid substrates. Those were some seriously determined birders. I dropped out of the line-up and crawled away in shame.

“Farewell, Spoon-billed Sandpiper, I thought to myself. I will see you another day.”

When we arrived at the restaurant, Daniela was waiting there, having chosen to sit out the Spoon-billed Sandpiper safari. She had returned alone, fearing a foot injury as a result of walking barefooted through the shoreline trash. Her safety concerns were valid. A puncture wound or minor skin laceration could quickly become infected and require medical attention.

Quý and I were unwilling to give up completely. It was early and the tide was still quite low. We knew where the mangrove inlet path was and it seemed possible to get out to the mudflats by the same route we had taken the previous afternoon. The only drawback would be doing the first part of the trek without a motorbike. Our local friend who had loaned us his motorbike, was nowhere to be found. So, we set out on foot from the Lovin’ Spoonbill cafe, blazing a pathway through a weedy fringe of tall grass and shrubs, an incidental buffer zone between the melon farms and mangrove.

We startled a large snake that gave us pause. The mystery serpent was partly concealed in low vegetation and instantly bolted out of our way. Quý reassured me there were no cobras around anymore. Quite possibly true. The Vietnamese have probably captured most of those iconic snakes for food or medicinal use. I have yet to see a wild cobra anywhere in Việt Nam. Street markets were probably the best places to find cobras and an assortment of other interesting reptiles.

Fast-forwarding the story, Quý and I eventually caught up with Bảo and the other birders on the mudflats. Paying abundant homage to Bảo, we took turns getting clear scope views of a busy little Spoon-billed Sandpiper, foraging frantically between mud puddles. I managed a few distant, blurry, diagnostic photos. The one – last- shot, do or die, ‘mission spoonie’ was complete and duly recorded.

In the blissful moment, all of my memorable and worldly life-bird adventures were eclipsed by this most remarkable one in Tân Thành. Quý‘ was ecstatic. In addition to a rite-of-passage spoonie, he had racked up a long list of life-shorebirds on this trip.

And, notably without much time to spare. On a swiftly changing tide, Quý and I needed to make a hasty retreat to the inner shore. Returning via the distant sandbar peninsula was no longer an option. A million years of accumulated river sediments had produced a mudpie about 1.5 km wide, where tidewaters sweep across with the terrifying speed of a tsunami. Locals were well aware of the danger. Bảo’s group had already arrived at the restaurant. He phoned Quý to warn us. Soon we could be trapped without a visible exit route.

We foolishly ignored Bảo’s advice for a few more precious moments and continued to observe and photograph shorebirds, widely scattered over the mudflats. The birds were so preoccupied with their tide-limited foraging schedule, that most of them simply ignored us. This was a shorebird student’s full immersion course. A wildlife photographer’s wet dream. Although time was fast running out for all but mudskippers, mollusks, crustaceans and marine worms, good fortune did not abandon us. There was yet a way out. A rapidly moving column of lady clammers showed us the way home.

Post script. Two days later, while at home in Đà Lạt, I discovered that Quý and I had actually made contact with a Spoon-billed Sandpiper resting on the northeast sandbar peninsula, during the first afternoon at high-tide. We had simply failed to distinguish it from the surrounding birds. The little dude was found in several digital camera images that I had hurriedly obtained, using the default ‘spray and pray’ technique of wildlife photography.

A Conservation Imperative

Comparing the two survey areas visited in the Mekong Delta, Tràm Chim and Tân Thành, clearly, the most urgent action needed is full protection of the migratory shorebirds of Tân Thành. Three recommendations are hereby given.

1) Discontinue and ban the unlawful use of broad-spectrum herbicides and pesticides on coastal farms. There are well known organic farming methods that would eliminate the leaching of toxic chemicals and their byproducts into the adjacent mangrove and tidal mudflats.

2) Except for legitimate scientific investigations, the use of bird nets on the Tân Thành sandbar peninsula and similar habitat in the Mekong Delta, should be discontinued and permanently prohibited. Existing wildlife protection laws must be strictly and consistently enforced.

3) Wildlife conservation education programs can be introduced in local schools and public meeting places. Ecotourism infrastructure, e.g. for increasingly popular and lucrative birding tours in Tân Thành, could be developed and maintained, providing seasonal income for locals and emphasizing sustainable harvesting of coastal resources, balanced with wildlife conservation.

Apparently, Vietnam wildlife protection agencies are unaware of, or for various reasons, unable to respond to immediate and long-term negative impacts resulting from the agricultural application of chemicals, in combination with immediately lethal impacts from the use of nets to capture shorebirds.

For example, among the many migratory shorebirds dependent on Vietnam’s coastal resources, our findings show that currently there are several globally endangered and threatened species in Tân Thành, such as, Malay Plover, Spoon-billed Sandpiper, Eurasian Curlew, Bar-tailed Godwit, Great Knot, Red Knot, and Curlew Sandpiper.

It is our sincere wish that this report finds its way to the appropriate resource agencies in Việt Nam, and that an effective action plan can be implemented without further delay.

Annotated Bird List

Mekong Delta: Tràm Chim National Park, Tam Nông Tinh ĐồngTháp; Tân Thành, Gò Công Đông, Việt Nam January 3-9, 2024 Callyn Yorke

………………………………………………………………………

LEGEND

Abundance: Numbers following each species entry are the highest count for a single survey, when two or more surveys at a particular location were made. Locations (see below) with the highest numerical abundance are listed first in the species accounts. When only one of us observed a particular bird species, their initials are given for that account (NHB; DLY; HBQ; CDY).

Frequency: C = Common, i.e. observed in half or more of the surveys in a given area; UC = Uncommon, i.e. observed in less than half of the surveys in a given area. Note, Tân Thành, was surveyed only twice on successive days, hence, indicating a species there as “common” or “uncommon” may differ from the results of a systematic series of similar winter surveys.

Age, sex and molt (when known): ad = adult; imm = immature; m = male; f = female; bsc plmg = basic (non-breeding plumage; alt plmg = alternate (breeding) plumage; trans = transitional plumage, i.e. basic into alternate plumage.

Survey Location Abbreviations (see preceding satellite maps and area descriptions): TT = Tân Thành, including outer shore, sandbar peninsula, mudflats, mangrove, coastal scrub, gardens and suburbs, modified and disturbed habitats; ubiq. = Ubiquitous in appropriate habitat; TCNP = Tràm Chim National Park, including waterways, lily ponds, mudflats and seasonal grasslands, marsh, Melaleuca and Eucalyptus woodland; WHGP = Wildbird Hotel grounds and adjacent pathways through habitats similar to TCNP. Note: the eastern portion of Area #1 of TCNP (about 50 ha, was visually surveyed from a WHGP elevated observation platform and adjoining pathways, used during walking surveys. Data for birds species observed within the park boundaries are designated as TCNP or WHGP/TCNP, when birds were in flight over both areas.

Ecology and Behavior: aerial insect hawking (ah); taking fruit, berries or parts of flowers (fr); gleaning insects from foliage (ig); probing on or beneath the surface (pr); estimated height (m) above ground (agl); gregarious (greg); mixed-species flock (msf).

Systematics and Nomenclature used herein, is an amalgam of Avibase, International Ornithological Congress (IOC) and current (2024) online resources, i.e. Birds of the World, Cornell University, USA.

Species of Special Concern, i.e. bird species currently listed by international conservation organizations (e.g. International Union for Conservation of Nature – IUCN) as, Endangered, Threatened, and/or Vulnerable, are given in bold-faced print. Abbreviations: NT = Near Threatened; VU = Vulnerable; EN = Endangered; CR = Critically Endangered.

………………………………………………………………………………………

Annotated Bird List

- Cotton Pygmy Goose Nettapus coromandelianus 24 m,f greg. pairs swimming/ feeding in lotus pond backwaters in msf with numerous other waterbirds, TCNP, C (photo).

- Garganey Spatula querquedula 8 greg, in flight (NHB), TCNP, UC.

- Indian Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhyncha 60 greg. swimming in lotus pond backwaters; in flight throughout, TCNP, C.

- Mallard Anas platyrhynchos (domestic, albino) 500 (conservative. est.) rural area wetlands around homesteads; mostly seen in transit between principal survey areas, greg. ubiq. C.

- Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 5 ad., imm, greg. pairs and individuals swimming in lotus pond backwaters; msf with numerous other waterbirds, TCNP, C.

- Feral Rock-pigeon Columba livia 100 + (conservative. est.) greg. small flocks of 3-5 in towns and villages throughout, seen mostly in transit between principal survey areas, ubiq. C.

- Red Turtle Dove Streptopelia tranquebarica 4 greg. on utility wires next to aquaculture ponds, TT, C.

- Eastern Spotted Dove Spilopelia chinensis 4 vocal, greg. in trees around buildings, gardens and a variety of modified habitats ubiq., C.

- Zebra Dove Geopelia striata 2 vocal, garden trees and clearings around buildings and modified habitat, WHGP, C.

- Green -pigeon Treron sp. c.f. vernans 2 relatively compact, small sized, seen briefly in fast flight above garden tree-tops (CDY), WHGP, UC.

- Large-tailed Nightjar Caprimulgus macrurus 1 repeatedly vocal; subsequently responding briefly to conspecific playback recordings; remaining well concealed and unseen in middle to upper level of mixed Cajeput woods with dense bamboo understory; made a brief flight, alighting in nearby tree and continuing to vocalize; encountered during a single night survey on north canal trail; not heard vocalizing elsewhere in the area, WHGP.

- Germain’s Swiftlet Aerodramus germani 500 + highly greg. flying 5 – 100m agl.; especially abundant in semi-rural areas near towns, e.g. TT; most if not all of these birds were probably semi-domesticated (i.e. farmed) and nesting in commercial buildings; no other swift species seen in areas where GESW occurred, except as noted in the following species account; ubiq; C.

- Swiftlet Collocalia sp. ? c.f. affinis 12, greg. ID (CDY): a tiny swiftlet with rounded wings and a short, square tail; significantly smaller in overall body size than GESW, showing more rapid, shallow wing strokes; in fading light the flight was very much bat-like, i.e. fast with multiple directional changes (I initially mistook these birds for bats); I observed the birds on two successive evenings at dusk, flying 10-20m agl, circling over garden trees and open areas around buildings; there were no GESW flying nearby for a direct comparison; WHGP. Note: Since there are presently no documented records of any Callocalia swiftlets in Vietnam, this is a tentative record, awaiting further verification and documentation, i.e. additional sightings, photos, specimens, etc..

- Greater Coucal Centropus sinensis 5 vocal, especially in the morning; sometimes sunning itself in a tall shrub in the morning, later often remaining hidden in dense vegetation bordering wetlands, WHGP; TCNP; C.

- Lesser Coucal Centropus bengalensis 1 in a tall shrub surrounded by marsh and grassland, TCNP; UC.

- Green-billed Malkoha Phaenicophaeus tristis 1 rather shy and secretive, hopping around in trees bordering waterways and gardens, WHGP;TCNP; UC.

- Western Koel Eudynamys scolopaceus 1 repeatedly vocal (unseen) at dawn and dusk, WHGP, C.

- Plaintive Cuckoo Cacomantis merulinus 2 vocal in trees adjacent to lotus ponds and gardens, WHGP; C.

- Slaty-breasted Rail Lewinia striata 2 furtive; occasionally vocal (alarm calls); seen only running in shallows of lotus ponds, WHGP; UC.

- White-breasted Waterhen Amaurornis phoenicurus 1 at the shoreline on a wooded embankment of the main slough, TCNP, UC (photo).

- Indochinese Swamphen Porphyrio viridis 120 loosely greg. often paired in lotus ponds; one pair engaged in an elaborate series of courtship postures for several minutes (photo); others apparently picking up wet surface vegetation as nest material, TCNP; C.

- Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropus 12 greg. swimming in lotus pond backwaters in msf with other waterbirds; TCNP; WHGP; C.

- Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala (NT) 3 in flight (NHB); TCNP; UC.

- Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans 60 greg. seen as individuals, pairs and in large flocks (50 +) soaring 50-150 m agl over wetlands, TCNP; WHGP; C (photo).

- Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus 24 (ad. imm) small flocks (2 -5) feeding (pr) in shallows of peat mudflats; larger flocks (10-12) seen in flight, 20-60 m agl over open fields, TCNP; C (photo).

- Yellow Bittern Ixobrychus sinensis 6 rather shy and secretive; solitary and in pairs or trios in lotus ponds and reeds at edge of sloughs, WHGP; TCNP; C.

- Black Bittern Ixobrychus flavicollis 1 furtive, on ground, partially concealed in dense vegetation on a wooded waterway embankment, TCNP; UC.

- Striated Heron Butorides striata 3 solitary on shorelines, mudflats, marsh and edge of mangrove, TT; TCNP; C.

- Chinese Pond Heron Ardeola bacchus 60 solitary and in pairs in a wide variety of wetland habitats; most abundant inland; TCNP; TCNP/WHGP; WHGP, TT; C.

- Eastern Cattle Egret Bubulcus coromandus 15 greg. in open marsh and grasslands, TCNP; C.

- Gray Heron Ardea cinerea 110 solitary in dawn flight and greg. in large flock (>100) in marsh bordered by tall trees for roosting, TCNP; C (photo).

- Purple Heron Ardea purpurea 20 (alt.; bsc. plmg) usually solitary, individuals widely separated in open fields and marsh, TCNP; C (photo).

- Eastern Great Egret Ardea modesta 10 solitary and in pairs, marsh and edges of waterways; shorelines, mudflats and mangrove; TCNP; TT; C (photo).

- Intermediate Egret Ardea intermedia 25 greg. pairs and small flocks in open wetlands, marsh, lotus ponds, edges of waterways; shorelines, mudflat channels and mangrove edge; TCNP; TCNP/WHGP; TT; C.

- Little Egret Egretta garzetta 60 solitary and in loose flocks in shallows at edge of lotus ponds, on mudflats, edge of mangrove and open wetlands; TCNP; TCNP/WBGP; TT; C.

- Little Cormorant Microcarbo niger 120 (ad, imm) greg. often found in pairs and small flocks perched with wings extended on trees and snags by waterways; TCNP; TCNP/WBGP;TT; C.

- Common Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo 3 (ad, imm) msf with LICO and INCO, perched in a tall tree overhanging main slough across from private aquaculture ponds, TCNP; UC.

- Indian Cormorant Phalacrocorax fuscicollis 3 (ad, imm) msf with other cormorants (see previous species account), TCNP; UC.

- Oriental Darter Anhinga melanogaster (NT) 3 perched on waterway snags; swimming and diving in canals, TCNP; TT; C (photo).

- Black-winged Stilt Himantopus himantopus 3 greg. foraging (pr) on mudflats with shallows at edge of lotus pond and reeds, TCNP; UC.

- Black-bellied (Grey) Plover Pluvialis squatarola 20 greg. a wary, cohesive flock on the sandbar peninsula at high-tide, readily flushed to the adjacent outer shore, TT; UC (photo).

- Little Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula 1 (bsc. plmg.) in large, msf of plovers and sandpipers on sandbar pen. at high-tide; TT; UC.

- Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus 13 greg. pairs on inner shore of sandbar peninsula at high-tide; TT; UC.

- White-faced Plover Charadrius dealbatus 7 individuals and pairs on sandbar and mudflats, TT; C (photo).

- Malay Plover Charadrius peronii (NT) 1 in msf with sandplovers and sandpipers on sandbar pen. at high-tide; TT; UC.

- Lesser Sandplover Charadrius atrifrons 350-400 greg. on sandbar peninsula at high- tide in msf; scattered flocks on mudflats at low-tide; TT; C.

- Greater Sandplover Charadrius leschenaulti 250 msf; individuals and small flocks on sandbar peninsula at high tide; mudflats at low-tide, TT; C.

- Pheasant-tailed Jacana Hydrophasianus chirurgus 4 (bsc. plmg.) foraging (pr) in backwater lotus ponds, peat mudflats, in msf with BWJA and other waterbirds, TCNP; C (photo).

- Bronze-winged Jacana Metropidius indicus 80 (ad, imm; bsc., alt. plmg.) loosely greg. in backwater lotus ponds and on mudflats; TCNP; C (photo).

- Eurasian Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus 14 individuals walking in shallows near the edge of the mangrove and breakwater at high-tide; at least ten more individuals resting with a flock of EUCU; TT; C.

- Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata (NT) 18 greg. two, nearly equal sized flocks standing and preening in shallows in front of the mangrove at high-tide; widely dispersed on mudflats at low-tide. TT; C (photo).

- Bar-tailed Godwit Limosa lapponica (NT) 30 greg. small, separated flocks of 4 -7 birds on inner shore of sandbar peninsula and base of breakwater at high-tide; a few flushed and flew nw, low over the shallows; TT; C (photo).

- Great Knot Calidris tenuirostris (E) 100 (conservative est.) greg. on mudflats and adjacent shallows at low-tide; in dense msf on sandbar peninsula at high-tide. TT; C (photo).

- Red Knot Calidris canutus (NT) 2 with GRKN on sandbar peninsula at high-tide; TT; UC (photo).

- Broad-billed Sandpiper Calidris falcinellus 8 greg. in loose, msf foraging (pr) on mudflats at low-tide; TT; UC.

- Curlew Sandpiper Calidris ferruginea (NT) 60 greg. in dense msf on sandbar peninsula at high-tide; small, cohesive flocks foraging (pr) on mudflats at low-tide; TT; C.

- Spoon-billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmaea (CR) 1-2; (Jan. 8 at high-tide): An individual resting on sandbar peninsula in msf with other shorebirds; a series of digital camera images showed that the resting spoonie stood up briefly when other shorebirds began moving around; (Jan. 9 at low-tide): An individual, possibly the same one from Jan. 8, was foraging (pr) on the mudflats between puddles at low-tide. The bird’s foraging posture was anteriorly inclined, often sharply, with continuous vibrating movements of the head and bill; the bill was usually inserted well below the mud surface, suggesting a preference for a comparatively soft, wet and pliable substrate. The food items taken when foraging could not be determined and were presumably quite small. Running rapidly, the bird occasionally changed foraging positions and locations, moving to a new area a few meters away with similar substrate features, either amongst or apart from other shorebirds, e.g. Greater Sandplover and Red-necked Stint. There were no leg bands seen on the Jan. 8 & 9 spoonies; TT; C (photos).

- Red-necked Stint Calidris ruficollis (NT) 80 (conservative est.) in dense msf on sandbar peninsula at high tide; pairs and small flocks scattered over large areas of mudflats at low-tide; TT; C.

- Terek Sandpiper Xenus cinereus 150 greg. pairs and small flocks in msf on sandbar peninsula at high-tide; pairs scattered over large areas of mudflat at low-tide; An individual found dead in upper level of a bird net on the sandbar peninsula (photo: 9 January 2024) TT; C.

- Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos 2 on inner and far outer shore of sandbar peninsula at high-tide; TT; UC.

- Common Greenshank Tringa nebularia 60 (conservative est.) individuals and small flocks in shallows at the edge of the mangrove and sandbar peninsula at low and high-tide; TT; C.

- Marsh Sandpiper Tringa stagnatalis 8 greg. in shallows in southwest section of the mudflats adjacent to mangrove; TT; C.

- Black-headed Gull Larus ridibundus 20 imm. – first cycle; ad. -bsc. plmg,) a loose flock flying low, circling lagoon; an individual standing alone on outer shore with nearby flock of terns, TT; UC (photos).

- Gull-billed Tern Gelochelidon nilotica 8 greg. on inner sandbar shore and outer shore with other terns at high-tide; TT; UC (photo).

- Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia 50 (bsc. and trans. alt. plmg.) greg. large, cohesive flocks taking flight from inner sandbar shore and mudflat shallows; outer shore with other terns, high and low-tide; TT; C (photo).

- Whiskered Tern Chlidonias hybrida 120 (ad., imm; bsc. & trans. plmg.) greg. in flight, low, into a headwind over sandbar and mudflats at high and low-tide; four individuals caught by sandbar mist nets; one live, netted bird was out of reach; another (photo, 9 Jan. 2024), badly tangled up and rather feisty, was liberated from a net and flew off across the outer shore; individuals circling low over lagoon (photo); TT; C.

- Greater Crested Tern Thalasseus bergii 4 (bsc. plmg.) greg. standing on outer shore, together with other terns at high-tide; TT; UC.

- Osprey Pandion haliaetus 1 perched on wooden pole in a shallow lagoon at high tide; circling over the area at low-tide; TT; C.

- Black-winged Kite Elanus caeruleus 1 (ad) in low flight over marsh and open field, TCNP; WBGP; UC (photo).

- Crested Serpent Eagle Spilornis cheela 1 in flight, about 20 m agl, over main, wooded slough and adjacent lotus ponds, TCNP; UC

- Eastern Marsh Harrier Circus spilonotus 2 (ad., imm) in low flight, 1 – 15m agl, over open marsh and grassland and adjacent waterways; TCNP; TCNP/WBGP; C.

- Black-eared Kite Milvus lineatus 5 greg. circling 10 – 20m over open reed beds, TCNP; UC (photo).

- Asian Green Bee-eater Merops orientalis 10 greg. sallying from 1-3m perch, open fields and edge of lotus ponds, TCNP; WBGP; C.

- Chestnut-headed Bee-eater Merops leschenaulti 1 (DLY); TCNP;C.

- Blue-tailed Bee-eater Merops philippinus 4 greg. sallying from 3-10m in trees bordering waterways and lotus ponds, TCNP; UC.

- Blue-eared Kingfisher Alcedo meninting 2 individuals perched on snags and making low sallies over water in shaded, wooded waterways, TCNP; C.

- Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis 2 on low snag perches along backwater ways TCNP; C.

- Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis 8 greg. pairs perched on berms and snags, mostly along dredged canals; readily flushed by our boat TCNP; C (photo).

- White-breasted Kingfisher Halcyon smyrnensis 6 perched 3 -15m in trees overhanging main slough and larger waterways with wooded embankments and adjacent lotus ponds; TCNP; WBGP; C.

- Black-capped Kingfisher Halcyon pileata 4 perched 2 – 4m agl; readily flushed from snags and in large trees overhanging main waterways bordered by lotus ponds; TCNP; C.

- Collared Kingfisher Todiramphus chloris 3 on posts, snags and flying low through mangrove and over adjacent mudflats near inner shore; TT; C (photo).

- Coppersmith Barbet Psilopogon haemacephalus 3 incessantly vocal for 10-15 minutes (unseen) in the mornings; wooded areas; WBGP; C.

- Freckle-breasted Woodpecker Dendrocopus analis 2 (m) ID notes: the vent of one bird, seen clearly at a distance of about 10m, appeared much brighter red than shown on text illustration, resembling more closely the recently separated, D. atratus of Central Việt Nam (Craik and Minh, p. 171); alighting on the lower tree level, moving up a Cajeput tree trunk and limbs; another seen in bamboo thickets with adjacent trees; WBGP; UC.

- Golden-bellied Gerygone Gerygone sulphurea 7 greg. vocal pairs in trees and shrubs, gardens and wooded edges of waterways; WBGP; C (photo).

- Common Iora Aegethina tiphia 2 in on wooded waterway embankment, foraging (ig) in foliage of Melaleuca and Eucalyptus trees, WBGP; UC.

- Sunda Pied Fantail Rhipidura javanica 3 greg. vocal, pairs often in msf with SEBU, BLDR, PLPR and other insectivorous birds, at all foliage height levels; one foraging (ig) on and near the ground in a streetside refuse container; WBGP; TT; C (photo).

- Black Drongo Dicrurus macrocercus 8 greg. pairs and trios perched on snags in open fields with adjacent lotus ponds; frequenting overgrown gardens and wooded edges of waterways; TCNP; WBGP; C.

- Northern Brown Shrike Lanius cristatus 2 one seen briefly, flying between trees in an overgrown garden; snag perch in open marsh and lotus pond; WBGP; TCNP; UC.

- Racquet-tailed Treepie Crypsirina temia 6 greg. shy and fleeting when approached; active in canopy and subcanopy of Melaleuca and Eucalyptus trees; occasionally lower in lotus pond garden shrubs; msf with SEBU and others, WBGP; TCNP; C (photo).

- Yellow-bellied Prinia Prinia flaviventris 6 greg. vocal pairs in reeds at edge of waterways; brushy buffer between mangrove and melon farms; TCNP;TT; C.

- Zitting Cisticola Cisticola tinnabulans 1 (DLY) open, reed field; TCNP; UC.

- Plain Prinia Prinia inornata 3 vocal individuals active in shrubs around lotus ponds, edges of clearings and in brushy understory of Melaleuca – Eucalyptus woods; TCNP; WBGP; C.

- Common Tailorbird Orthotomus sutorius 2 vocal, though secretive in wooded areas with dense understory; gardens and edges of clearings; WBGP; TT; C.

- Black-browed Reed-warbler Acrocephalus bistrigiceps 1 active in low to mid heights in Melaleuca foliage, WBGT; UC (photo).

- Oriental Reed Warbler Acrocephalus orientalis 5 vocal, greg. individuals and pairs active in brushy edges of clearings and margins of lotus ponds; TCNP; WBGP; TT; C.

- Striated Grassbird Megalurus palustris 12 vocal – sounding remarkably similar to the unrelated Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris) of North America, which occupies an ecologically equivalent habitat. Eugene Morton’s pioneering studies of bird vocalization characteristics in differing habitats (e.g. American Naturalist 1975, (109): 965), suggested that convergent vocalizations in geographically and taxonomically separated bird species, reflect similar acoustical properties of their respective environments; vocalizing STGR at this location were observed in reed beds and edges of lotus ponds; grassy margins of waterways bordering large, open fields; TCNP; C.

- Eurasian Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica 20-70 greg. flying low over waterways and adjacent lotus ponds; open marshland and a variety of wetlands; ubiq; C.

- Sunda Yellow-vented Bulbul Pycnonotus analis 10 vocal, greg. occupying a wide range of modified habitats; frequenting all foliage height levels in search of fruit and insects; often joining msf; ubiq; C.

- Streak-eared Bulbul Pycnonotus conradi 20 vocal, greg. similar behavioral ecology as SYVB (see above), though restricted to denser vegetation than SYVB when sympatric and sometimes the numerically predominant bulbul species in those areas, e.g. WBGP; TCNP; C (photo).

- Dusky Warbler Phylloscopus fuscatus 1 on and near the ground in wooded margin of a shady waterway, TCNP; UC.

- Radde’s Warbler Phylloscopus schwarzi 1 similar behavior as DUWA (see previous species account) staying low on and near the ground in a Melaleuca stand bordering a drainage ditch, WBGP; UC.

- Pale-legged Leaf-warbler Phylloscopus tenellipes 1 (NHB); TCNP; UC.

- Arctic Warbler Phylloscopus borealis 1 foraging (1g) quickly in Melaleuca foliage, 3 -5m agl; WBGP; UC.

- White-shouldered Starling Sturnia sinensis 12 vocal, greg. in Melaleuca and Eucalyptus canopies, often with BLDR and SEBU; WBGP; UC.

- Common Myna Acridotheres tristis 10 vocal, greg. on ground and buildings; ubiq; C.

- Oriental Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis 2 vocal, though rather shy; in gardens and second-growth at edge of woodlands, WBGP; TCNP; C.

- Asian Brown Flycatcher Muscicapa dauurica 2 sallying from mid-level limbs of Melaleuca trees; WBGP; C.

- Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula albicila 1 (DLY) TCNP; UC.

- Japanese (Amur) Stonechat Saxicola stejnegeri 2 (m,f) a pair, each perched atop adjacent shrubs at edge of main slough and lotus pond; TCNP; UC (photo).

- Ornate Sunbird Cinnyris ornatus 2 (m,f) vocal, mid to upper levels of Melaleuca trees; garden shrubs; WBGP; UC.

- Brown-throated Sunbird Anthreptes malacensis 1 (DLY) TCNP; UC.

- White-rumped Munia Lonchura striata 5 greg. in shrubs at edge of lotus pond; WBGP; UC.

- Scaly-breasted Munia Lonchura striata 4 greg. in tall grass and shrubs at edge of clearings and farms; WBGP; TT; UC.

- Eurasian Tree Sparrow Passer montanus 20 (m,f) vocal; on ground, buildings and trees; in villages and towns throughout the region; TT; C.

- Forest Wagtail Dendronanthus indicus 1 seen once on path through wooded area; flushed to trees; WBGP; UC.

- Paddyfield Pipit Anthus rufulus 5 a pair on ground in melon farm; TT; C.