Sarawak,(Borneo) Malaysia Trip Report, 15-30 August, 2023 Callyn Yorke

Scroll down for the Annotated Bird List

Introduction

Zoologists, naturalists and wildlife photographers often suffer from a chronic condition known as temporary tunnel vision, caused by a world where there is everywhere an alarming loss of biodiversity. Nowhere is this loss more glaringly apparent than in Southeast Asia. In this brief visit to Borneo, I attempted to capture images of some of the most stunning wildlife remaining on the planet, bringing into focus an urgent need for habitat and wildlife conservation. Anecdotal observations and remarks frame some of the more interesting subjects captured as digital images.

Massive destruction and modification of natural habitat was well underway before I first arrived in West Malaysia in March of 1977. Vast areas of lowland rainforest had been converted to rubber-tree plantation; oil palm, a globally lucrative product, was appearing as its primary monoculture replacement. Mining (tin, antimony, gold, mercury, aggregate rock and coal) continued to take huge bites out of the landscape. The outlook for ecological conservation in Malaysia was bleak indeed, and qualitatively quite different from the days when the first waves of Europeans arrived in the East Indies.

Gathorne, Earl of Cranbrook writes the following (Malaysian Naturalist, Vol. 75(2) & 76(1), 2021-22, p.167):

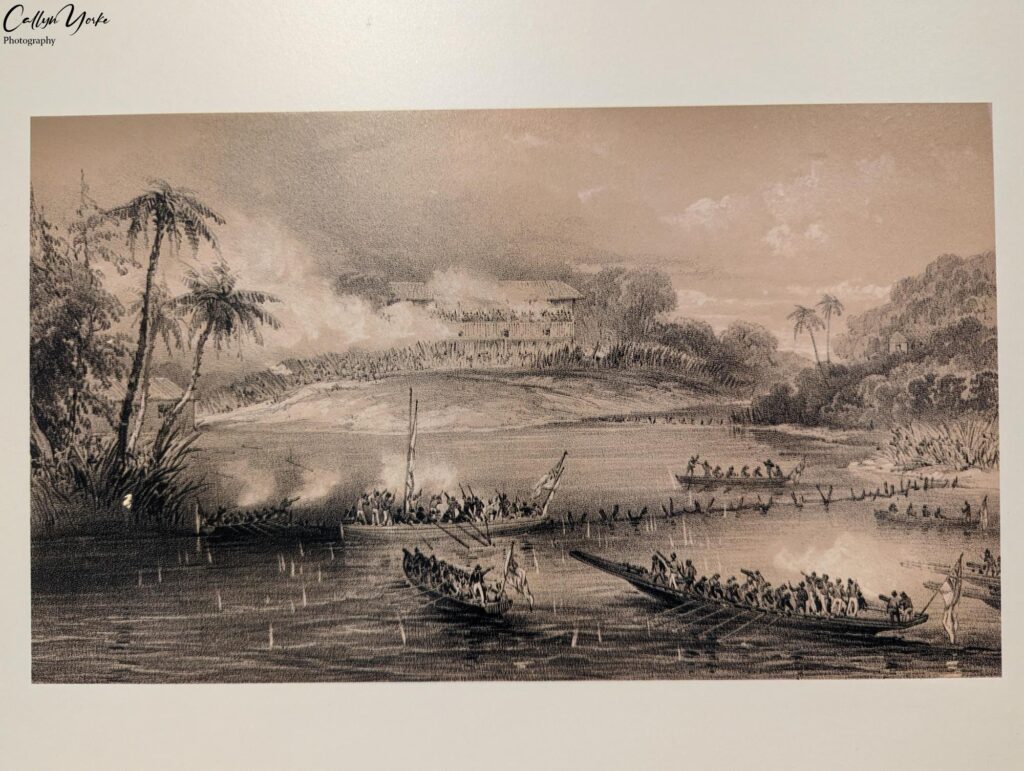

On 11th August 1838, James Brooke, aboard his armed schooner Royalist, entered the Santubong mouth of the Sarawak river. He wrote in his diary: ” The scenery is noble. On the left hand is the peak of Santubong, clothed in verdure nearly to the top; at his foot, a luxuriant vegetation, fringed with casaurinas, and terminating in a beach of white sand. The right bank of the river is low, covered in pale green mangroves.” On the 12th August, Brooke went ashore with his gun, making his first observations of the wildlife: “There was a fine species of large pigeon of a grey colour [Ducula pickeringii ?] that I was desirous of getting; but they were too cunning. Plenty of wild hogs were seen [probably Sus barbatus], but as shy as though they had been fired on all their lives.“

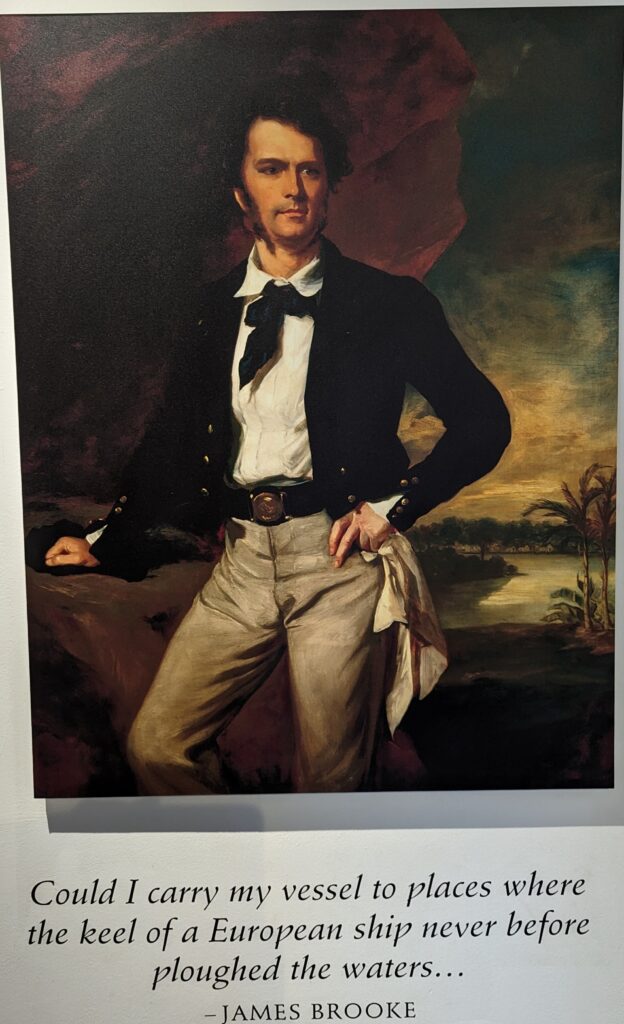

East Malaysia, comprising the states of Sarawak and Sabah on the island of Borneo, had also been targeted by European merchants and fortune hunters, e.g. James Brooke and his descendants. Those folk’s primary interest appeared to be profiteering, incidentally at the expense of both the indigenous people and the natural resources upon which they depended. This pattern of exploitation continues today in Borneo, though perhaps slowed slightly by an increasing awareness of the uniqueness of the flora and fauna found there.

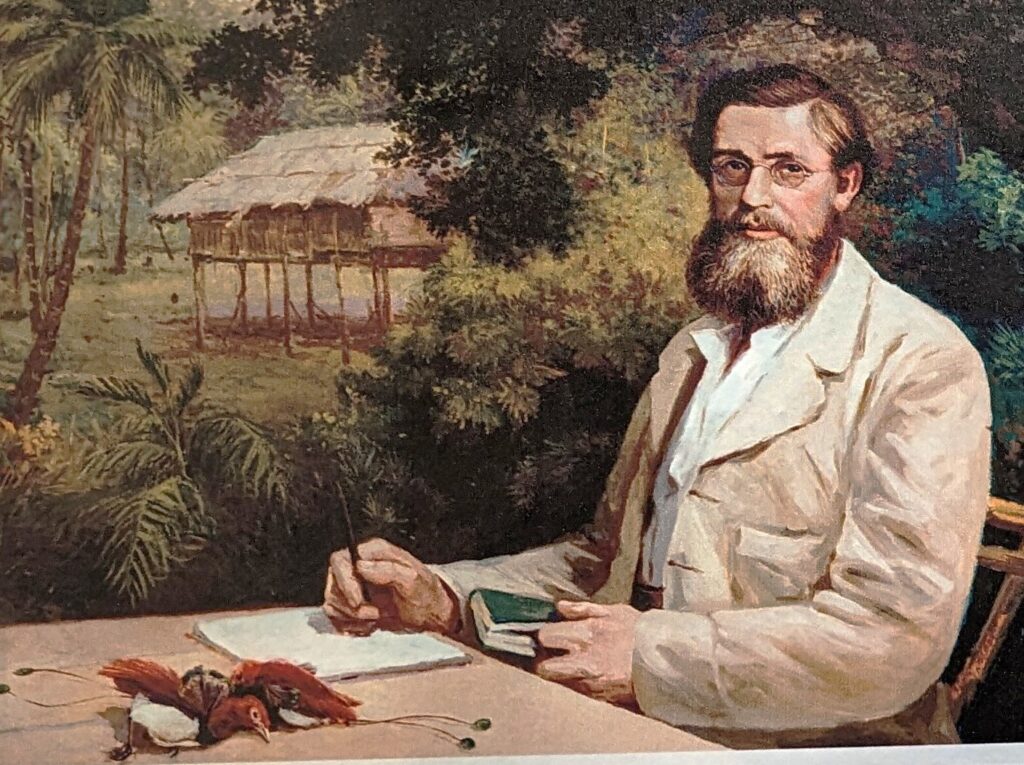

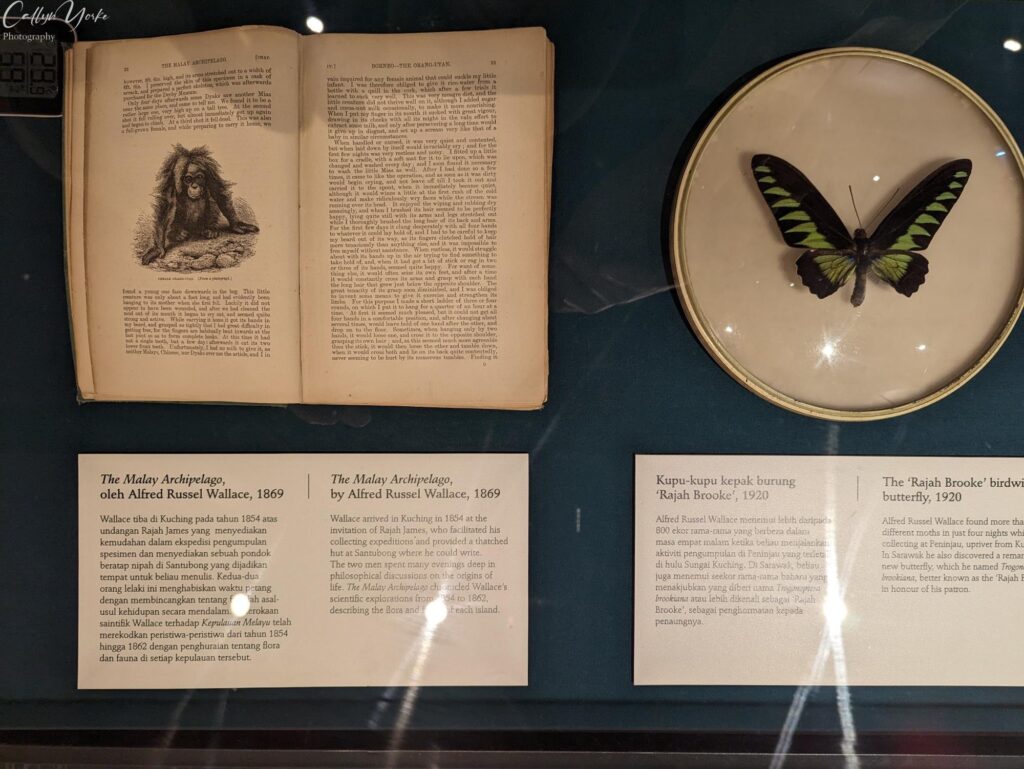

Counterbalancing colonial resource exploitation, a series of European naturalists visited Borneo and made substantial contributions to catalogues of biodiversity, largely kept by museums in their home countries. Among them, was the Englishman Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), who spent time in Sarawak (1854-1856) collecting zoological specimens, many of which carry his name into perpetuity.

Wallace, of course is acknowledged for independently deriving a version of evolution by natural selection, simultaneously championed by Charles Darwin. Wallace, a phenomenally prolific collector. Using a lantern next to building with a white wall, he reportedly obtained eight-hundred species of moth during a period of eight consecutive nights in Sarawak. Suffering feverish bouts of illness, he also managed to document his ideas about speciation, i.e. the ‘Sarawak Law’ (1855).

At about that time, an intriguing, long-distance relationship between Wallace and Darwin began to develop. The story of what happened between them has been told many times and unsurprisingly, with a variety of interpretations. To summarize, when Darwin became aware of Wallace’s intention to publish further on the subject of speciation, he wrote to Wallace attempting to defend his intellectual territory; Darwin was urged by at least one prominent colleague, Charles Lyell, to complete his magnum opus, Origin of the Species (1859). Science sometimes results in a down and dirty dog fight, particularly when there is an important new discovery to be published. Darwin and Wallace probably realized the potential for a skirmish over intellectual propriety, but were honorable enough to find a civilized compromise.

The two men eventually met in England and agreed to jointly present a formal paper on the subject they had both independently spent a good deal of time thinking about: How new species arise. And by the way, although Darwin supported his thesis with an abundance of examples from both domestic and wild organisms, neither he nor Wallace ever had a clue about the fundamental principles of inheritance, published (in German) in 1865 by an Austrian monk, Gregor Mendel (curiously, a copy of Mendel’s publication was later found in Darwin’s library). Had Wallace or Darwin known of Mendel’s ground-breaking work on inheritance in garden peas, they probably would have understood its profound relevance to the missing piece of the puzzle: a biological mechanism for evolution (Mendel evidently knew of Darwin’s work but, perhaps due to his religious beliefs, dismissed it as interesting speculation).

Through subsequent decades, Wallace’s name faded into comparative obscurity as Darwin received much attention for his own pioneering work in Biology. In recent years, Wallace’s image has received a face-lift, culminating with the installation of his portrait next to Darwin’s in the British Museum of Natural History, London.

Furthermore, Wallace’s most famous publication, The Malay Archipelago (1869), undoubtedly stimulated considerable interest in the natural history of the region. That was certainly true in my case as a young zoology graduate student in California. I had long been fascinated by the incredible faunal diversity of Southeast Asia, so eloquently described by Wallace and other naturalists working in that region. After completing a Master’s Degree in Biology, I enlisted as a USA Peace Corps Volunteer for a three-year teaching term with Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur (1977-80). There were frequent opportunities for research and travel in the region, which I embraced with great enthusiasm, including a trip to Sabah and multiple journeys through the Indonesian islands. For some reason, however, I bypassed Sarawak. And now, finally, decades later, that oversight would be corrected.

Visiting Sarawak for the first time, this journey would be an opportunity for me to glimpse some of the grandeur that Wallace found there nearly 170 years earlier. The thematic phrase here is “some of the grandeur.” Much has changed in Malaysia, if considering only the past forty years.

Knowing a bit about Wallace and other European 19th century explorers in Sarawak, e.g. Marquis Giacomo Doria, Odoardo Beccari, Alfred Hart Everett, and botanical artist, Marianne North, I greatly anticipated a visit to the local museums in Kuching. Two of those historic establishments are perhaps among the least popular museums in Kuching, when compared with the adjacent, ultra-modern Borneo Cultures Museum. The two older museums were rather dilapidated and cramped, yet housed uniquely significant collections. I couldn’t decide which one, The musty old Sarawak Natural History Museum, or the tiny Fort Margherita Museum, was the most informative and worthwhile; in both places I found myself mostly alone to enjoy the exhibits.

As might be expected, the dimly lit, slightly dank Sarawak Natural History Museum had a crowded series of wooden framed glass cases with handwritten labels on zoological specimens, some dating back to the 19th century and showing their age, including obsolete nomenclature. Most of the stuffed and mounted birds were recognizable, though rather tattered, shrunken and faded. A glass walled closet near the front door, was perhaps the most surprising exhibit – a collection of Wallace’s field gear and a handful of his specimens.

This was a real museum in the traditional sense. No catchy audiovisual effects, e.g. large-screens with video loops; no tour-guides leading scores of visitors through the exhibits. Overshadowed by the neighboring Borneo Cultures Museum, the modest Sarawak Natural History Museum featured thousands of preserved specimens, weatherng the equatorial elements quietly, gracefully, largely unnoticed by all but a few curious naturalists and other travelers searching for the hidden gems of Kuching.

A few days later, after surveying birds in the Sarawak Botanical Gardens, I walked over to the nearby Fort Margherita Museum. At first, the museum appeared to be only two small rooms at the entrance with a model schooner in a glass case, surrounded by 19th century artwork and early 20th century photography, mostly produced in Sarawak. A couple of renovated jail cells were outside, where a Malay family took turns imprisoning themselves for photos. Was that it? Not quite. As I was leaving, I noticed an adjacent cubby with a spiral staircase. A young man collecting admittance fees ($10 MYR) indicated that there were more exhibits upstairs. Indeed, there were. In fact, most of the museum was upstairs — accessible only by this dizzyingly narrow, lighthouse-style staircase. No one else at the museum that morning seemed motivated to climb it.

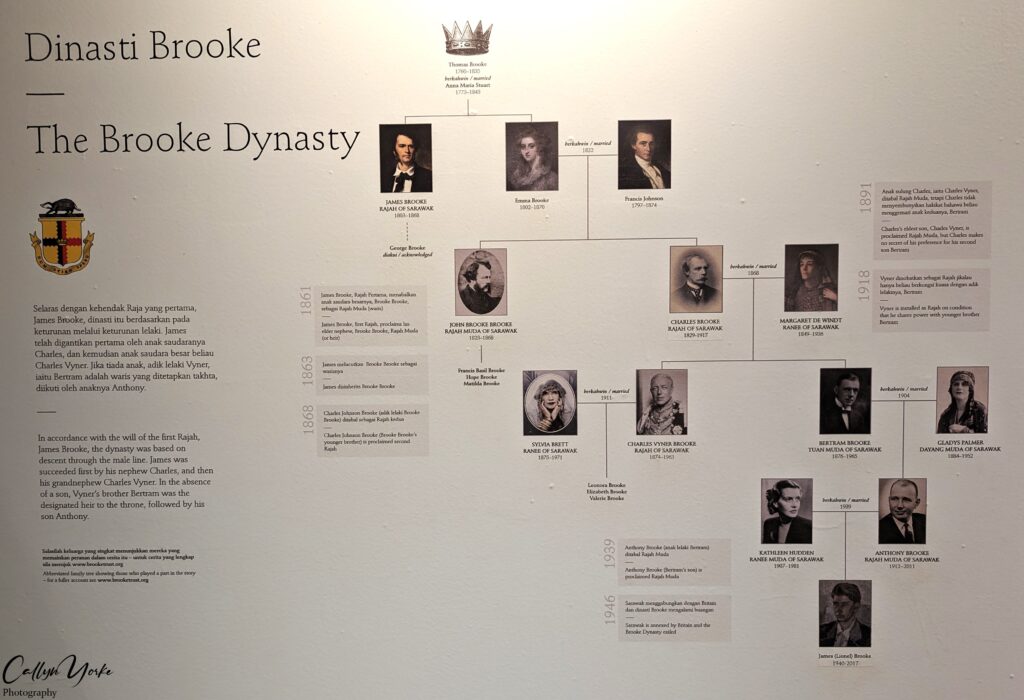

Three more levels in a tower with small rooms held a series of fascinating exhibits, including local artifacts, weapons, paintings and photos, describing the colorful history of Sarawak, particularly Kuching, a traditional trading port. One of the rooms contained a detailed history of the Brooke dynasty – an English family who governed Sarawak for three generations (1842-1946), beginning with Raja James Brooke (see family tree photo below).

James Brooke, with governing interests primarily as a businessman, and with the looks and lifestyle of a poster-boy for a Hollywood swashbuckler, first met Alfred Russel Wallace in Singapore in 1854, who was beginning a zoological expedition of the East Indies. Raja Brooke must have taken an immediate liking to Wallace and invited him to his kingdom in Sarawak. Wallace accepted and settled initially in Santubong, where he immediately began collecting many new zoological specimens for the British Museum and wealthy customers in Europe.

Moth and butterfly sales probably helped finance Wallace’s living and local travel expenses. But the big-ticket items were orangutan specimens. Of the latter, Wallace’s sales included three orangutans he shot in Sarawak forests, a female and infant, then a small male, earning him nearly £100. He also sold a few orangutan skins, skulls and skeletons to the Derby Museum of Liverpool for the sum of £150.

Just as an aside, British folks today are acutely aware of their devalued quid. Since 1850, the British Pound has lost 99.4% of its value. In Wallace’s time, £1 had 172 times the purchasing power as it does today; £100 in those days would be equivalent to about £17,223 today, a small fortune. By almost any measure, Mr. Wallace was a successful businessman in his own rite.

Sadly, wild orangutans are rarely seen in Sarawak anymore. I spent one morning in the Semenggoh Nature Reserve, which has been for decades used as a rehabilitation center for rescued captive orangutans. A substantial number of orangs were born there, now roaming freely in the forest, occasionally returning to an elevated wooden stage showcased beneath ropes secured to large trees. About one-hundred twenty tourists were there the morning of my visit. But only one teenage orangutan appeared for breakfast (photos). ‘Canza’ was the star of the show that morning, doing a slow and deliberate series of acrobatics on the ropes, though mostly just contentedly hanging out for photos.

The staff at Semenggoh recognize all of the orangs (unlike birds, individual orangutans have remarkably distinctive craniofacial features), each photographed, adorably named and catalogued. Some of the animals are apparently comfortable living in the Semenggoh forest and make regular visits to the feeding station. Others disappear and may not be seen again for years. Signs at the entrance of the preserve, warn that visitors may not be lucky enough observe any orangutans, especially during the summer fruiting season. No problem. I had seen and photographed orangs in Sumatra in the late ’70s (Sumatran orangutans, based largely on molecular differences, are now considered a separate species); those were within a remote, semi-wild forest rehab center that seldom received visitors. I spent a three nights there sleeping on the concrete floor of a storage shed.

Birds were my primary interest in Semenggoh, since it was a comparatively pristine lowland rainforest, thirty-minutes by taxi from Kuching. An online bird list for the nature preserve showed an impressive 213 species. Naturally, one would expect to find only an infinitesimal fraction of those during a single visit. And that’s just about what I came up with (around thirteen species), including a lifer, Black-bellied Malkoha, quite distant in a tree canopy, harshly backlit, perhaps 30m above ground-level. The other prize for me, unrealized at the time, was an Oriental Pied Hornbill. Except for numerous statues and stuffed specimens in Kuching, it was the only hornbill I saw during my two-weeks of daily field surveys in Sarawak. I would have liked to stay longer in Semenggoh, but the hours of operation were limited to 8-10 am and 2-4 pm. No tourists were allowed in the reserve outside of those time frames. The schedule was strictly enforced. Plain-clothes employees kept a close watch on me and the other visitors. We were herded out of the orang feeding station and back to the main gate and souvenir kiosks promptly at 0930 hrs.. I imagine that Wallace would scarcely recognize Sarawak and make a hasty retreat back to his grave.

Comparing Kuching today with the historic photos of it in the Fort Margherita Museum, shows what runaway commercial development can do to one of the most interesting and diverse lowland rainforest ecosystems in the world. Where a riverine gallery forest once bordered the town, there are now only scattered, small islands of second-growth, some designated as parks and natural areas.

Highly vigilant, opportunistic and adaptable creatures may be found in and around Kuching today, which includes introduced species, e.g. Feral Rock Dove, Common Myna, Javan Myna and unsurprisingly a sizeable population of feral cats, the namesake of the city (kuching is the word for cat in Bahasa Malaysia) .

Unsure of lodging options in and around the west Sarawak national parks (Bako National Park was fully booked; Kubah National Park was closed indefinitely for lodging; Borneo Highlands Resort was completely closed), I reserved a room in downtown Kuching at the Hotel Longhouse (3 stars, US$25 per night). That turned out to be a reasonably good alternative; day-trips to distant locations, e.g. Bako NP, were readily arranged by the friendly hotel staff. Once I had the Grab Taxi app. downloaded on my phone, getting around town to the parks and other points of interest was fairly simple, efficient and affordable. One particular Grab Taxi driver, Mr. Bong, became my regular driver for transport to the relatively distant and remote birding areas out of town, e.g. Sejingkat ash ponds. Using Google Maps and online publications with information about natural areas, I systematically visited a number of places where birds and other wildlife could be found and photographed.

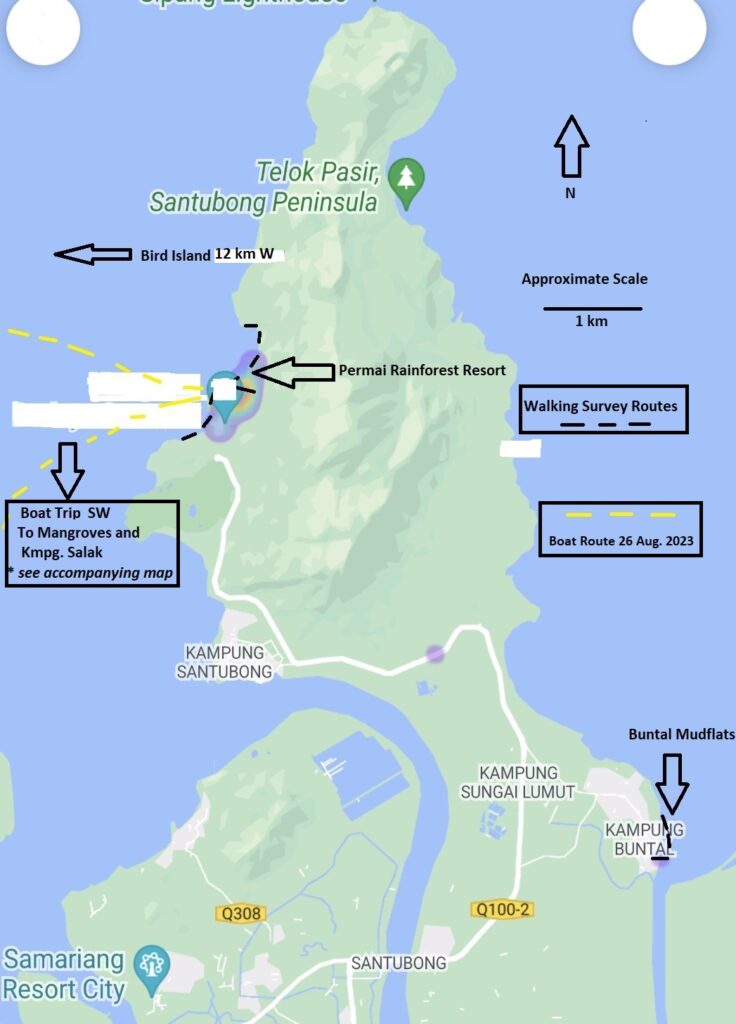

On August 22, before visiting the Buntal mudflats, Mr. Bong drove me to the Permai Rainforest Resort at the foot of Santubong Mountain (this area was briefly described by James Brooke in his diary entry quoted above; presumably this is also where Wallace initially lived in Sarawak. I walked around the resort, bordered by a scenic, rocky coastline on the west side and a mature rainforest to the east. A series of elevated cabins in the forest overlooking the bay were being used for lodging. The place looked perfect for me — a variety of habitats to explore in a relatively quiet, rustic resort. (two-star, US$75 per day, including breakfast and full access to the trails and facilities). I booked a ‘treehouse’ there for five nights at the end of my two-week visit to Sarawak. It was definitely one of the highlights of the trip.

Survey Areas, Dates, Methods and Materials

The following is a summary of my survey locations in Sarawak, and except for specific Kuching locations, are given in chronological order. Each area is given an abbreviation used in mapping and in the Annotated Bird List. Except for the Permai Rainforest Resort, Kuching Waterfront and Hotel Longhouse neighborhood, which were surveyed daily, the remaining locations were visited only once (see below for further details).

Weather during the morning surveys was fairly consistent: overcast to partly cloudy with intermittent drizzle and/or light rain; PM surveys were often abbreviated due to afternoon and evening thundershowers, heavy at times. Ambient air temperature, 25°C to 32°C. Winds were variable and generally light (2 -10 kph), W, WNW, SSE. Seas were calm to moderately choppy.

For surveys, I used a Zeiss 10×42 binocular, Nikon D850 with a Nikon PF 500mm lens; occasionally a Nikon 60mm Micro lens; Google Pixel 7 Pro and Google Pixel 3X cell phone cameras were used for documenting habitats, vegetation, signage and items of interest; those images included GPS metadata, subsequently used for mapping locations and survey routes (see area maps below). A pocket field notebook was used during the surveys; handwritten notes were recopied each evening into a 22 cm x 14 cm permanent, loose-leaf binder format. Field notes and digital images obtained during the surveys formed the basis for this report.

Survey Locations (August 16 – 29, 2023)

Kuching (August 16- 24; 29): Including the Hotel Longhouse neighborhood (HLH) and Waterfront (KWF). This is a highly urbanized area with heavy traffic. Green strips separating roadways and along the waterfront, included mature, flowering trees and shrubs (mostly exotic). Weedy vacant lots and mowed grasses occurred throughout the city and were often attractive to birds, e.g. Eastern Spotted Dove, Zebra Dove, Tree Sparrow, Javan Myna and Common Myna.

While in residence at the Hotel Longhouse, I usually walked the backstreets and side streets two or three times a day, including dusk and dawn. I once used a sampan taxi to cross the Sarawak river between the riverside kampung below Ft. Margherita and commercial Waterfront ($US 0.25). The Sarawak river at the Waterfront seldom had any observable birdlife, except where it was bordered by trees and weedy second-growth. Gardens, trees and lawns along the Waterfront walkway attracted a small variety of common, highly urbanized birds noted above.

The survey areas in Kuching also included the Borneo Cultures Museum and grounds (BCM), Sarawak Natural History Museum and grounds (SNHM), and the Darul Hana pedestrian bridge. Other survey areas in Kuching, i.e. Kuching Reservoir Park (KRP), Kuching Botanical Gardens (KBG) and Orchid Park (OP), are described separately (see following accounts).

Kuching Reservoir Park (KRP, August 18, 2023: 0743-0902 hrs.)

Although this large urban park featured ponds, marginal marsh and patches of mature rainforest with fruiting fig trees, I found the birdlife there to be rather impoverished. I walked the paved pathways in the park, through swarms of mosquitoes, surveying the varied habitats carefully for signs of life. But everywhere people were jogging and talking, sometimes shouting and waving their arms, apparently engaged in their daily exercise routines. Such activities doubtless reduced bird presence and detectability. Overall, this park was disappointing as a birding destination in Kuching. I continued down to the waterfront, which was only a few minutes walk from the park. There were just about as many bird species found along the waterfront as in the park, though composed of different species.

Sarawak Botanical Garden (Taman Rekreasi Wisma Bapa) SBG, August 20, 2023: 0810-1200 hrs.

This large, urban park was by far the best birding location I found in Kuching. The property included lawns, open fields, patches of woodland with mature fruiting trees (native and exotic), drainages, a large swamp and lily pond with marshy borders; marginal second-growth occurred in a few spots, especially adjacent to a drainage on the southern boundary.

In short, there was plenty of food and cover for birds. The park was quiet and largely undisturbed during the survey; fewer than ten other persons were present. I practically had the entire place to myself. I visually surveyed most of the park, covering an area of about 25 hectares.

Orchid Park, Kuching (OP, August 24, 2023: 0820-1025 hrs.)

This small, intensively maintained garden park, combined with adjacent property, contained a large variety of cultivated orchids (many flowering) and other plants, including native and non-native shrubs and trees. A gardening crew was busy watering and trimming vegetation during my survey. Flowerpeckers and sunbirds were occasionally heard and seen briefly visiting flowering plants; larger bird species, e.g. Eastern Spotted Dove and Asian Koel, vocalized but avoided the garden, instead favoring adjacent tall trees. Prior to the park opening time (0930 hrs.) I walked the northern border, surveying birds in decorative shrubs and trees around the parking lot and across the roadway. I did not see any other visitors in the park gardens during my survey. Overall, this was a worthwhile birding location, largely because of an opportunity for photographing the Bornean Black Magpie, a near-endemic species that was elsewhere shy and fleeting.

Semenggoh Nature Reserve, Sarawak (SNR, August 16, 2023: 0825-1030 hrs.)

I made one weekday visit to this popular forest reserve. Prior to the gates opening, busses and taxis released dozens of tourists, some of whom queued up with me at the ticket booth ($5 foreigner fee). A cellphone barcode reader was necessary for registration. Several electric shuttle vehicles awaited crowds heading for the orangutan feeding station — the main attraction for most visitors.

I chose to walk the roadway through the forest and bird along the way, about 1.5 km to the feeding station. A few others did the same, although I was apparently the only one with a binocular and looking specifically for birds. Most of the birds I encountered were vocalizing and unseen. A few birds foraged in the distant canopies of fruiting fig trees. The lighting was suboptimal for photography — either too little in the forest understory, or too much backlighting in the in the canopy. Brief, distant glimpses of birds in flight were mostly what I obtained; few of them resulted in positive identifications. Aside from fairly good photo opportunities with a semi-tame orangutan named Canza at the feeding station, there wasn’t much else for me to do during the brief, two-hour visit in Semenggoh. There appeared to be no good reason for making a return trip here from Kuching.

Bako National Park, Sarawak (BNP, August 17, 2023: 0830-1500 hrs.)

This day-trip involved a 40-minute taxi ride to a shuttle station next to the Bako kampung, followed by a 30-minute motorboat trip to the Bako National Park headquarters. Both segments of the journey to the park went without incident. The timing was good. Two young Spanish couples at the shuttle station were ready to share the roundtrip boat fare: the total cost for all five of us, $200 MYR. My share was $40 MYR, about $US 8.90.

Due to the low tide, our boat stopped about 50m short of land. That meant we would need to remove our shoes and wade to the shore. Ordinarily, that wasn’t problem. But with my binocular, camera gear, backpack and boots, I needed some help getting in and out of the boat. Images of having dunked my camera in the sea some years earlier, came flooding back to me. Happily, one of the boatmen was there to assist me by taking my boots, which freed my hands to balance and keep my gear out of the water. And shortly thereafter I would be making good use of my camera in Bako.

I checked into the ranger station, obtained a map and recommendations for where to find birds and wildlife. One of the park rangers suggested I walk north on the beach to find Proboscis Monkey; a male had recently been seen in that area. He mentioned that the trails around the headquarters should be good for finding birds and obtaining photographs. That was fine with me. In my experience, long hikes on park trails were exhausting and unproductive, compared with what can often be found and photographed at close range near park headquarters.

Since the endemic Proboscis Monkey would be a life-mammal for me, photos of the A-lister celebrity primate were highly desirable. I headed north on the wide, sandy beach, scanning the casuarinas and beach scrub for any signs of life. But after about 45-minutes of intensive searching in the blazing sun, it was clear that, if the animal was around, it was making itself invisible to me. Meanwhile, at the south end of the beach, about 1km from where I stood, a small crowd of tourists stared and pointed at something in the dense vegetation. I hustled over there and sure enough, a male Proboscis Monkey, mostly concealed by vegetation, was munching on yellow flowers of a small tree. I could see fragments of the animal — an arm, a shoulder, hindquarters, back of the head — in the shady tangles of the tree understory, and that was about all. A few minutes later, it retreated completely out of view into the adjacent woodland. I needed a much better view and photo opportunity than what this shy creature fleeing the Paparazzi was willing to provide.

Meanwhile, there were other subjects of interest. At the north end of the main beach, a murky mangrove estuary crossing included an adjacent covered seating area that was a welcomed relief from the midday heat. While gazing at the stream bank, I noticed several juvenile and adult mudskippers swimming and scooting over the mud. They were a bit too small and distant for obtaining identifiable photos. Through my binocular I could see that adult mudskippers had a elevated bulbous structure on their snouts (accessory air storage?) and morphologically appeared to be an entirely different species (quite possibly a different genus) than the mudskippers I had seen recently in Taiwan.

Birds were fairly active in the shrubs and trees around clearings for buildings and walkways. I was adding new ones to my list with some regularity — Olive-winged Bulbul, Magpie Robin, Asian Fairy Bluebird, Orange-bellied Flowerpecker and, a common species I had not yet seen in Sarawak, Bold-streaked Tit-babbler. Vocalizations of other, unidentified birds wafted in from the surrounding forest. With patience, I would eventually make visual contact with some of them.

While resting in the shade and reviewing my camera images, a member of the park staff approached me excitedly and asked me to follow him to an area behind an office building. There, at eye-level, coiled on a limb of a small tree, was something new. An endemic Bornean Pit Viper. The snake’s nearly uniform lime-green coloration matched the foliage so well, that one might easily walk right by it — or right into it. Yikes! The lighting and position of the snake were good. I changed lenses and crept in slowly for a series of close-up shots. The snake didn’t move a millimeter, give a tongue-flick, or show any signs of being aware of my presence. I guess if I wasn’t on the menu and didn’t shake its tree, whatever it judged me to be, I was a nonstarter.

Diurnal vipers generally have good eyesight and highly evolved chemosensory and thermo-sensory software on board, improving the accuracy of their strike. They could use one sensory upgrade, perhaps. Snakes, having evolved from fossorial or possibly fully aquatic lizards, lack external ear openings and are legally deaf. That particular handicap is a good sign, pardon the pun, because the older Nikon cameras like mine produce a mirror-slap that can be heard from several meters away. Click, click, click. Amazing. Click, Click. Soon I was joined by a Frenchman with similar herpetological interests and camera equipment. It was his turn to step up for some nice shots of this infinitely patient and understanding reptile.

Minutes later, a small crowd gathered at the edge of the forest behind the guest lodges. A park ranger had spotted a lone female Proboscis Monkey in the subcanopy. The distance was a challenge — all of the Nikon PF 500mm lens would be needed; there was just enough space between branches and adequate sunlight filtering through the canopy for some decent head shots of the animal. Yes. This was finally a view and photo opportunity for Proboscis Monkey that I had been seeking. Incredible.

Nearby, a troupe of about twenty Silvered Leaf Monkey was eating foliage from a small tree at the edge of the forest. Several youngsters were among them, practicing their arboreal moves and sampling the vegetation.

Three o’clock arrived sooner than I expected and it was time to find my Spanish companions and our boat back to the shuttle station. Bako had been an interesting and productive day-trip. Perhaps a few more days in the park would have been equally amusing. Oh well. Maybe next time there will be lodging vacancies in the park. Curiously, many of the lodge rooms at park headquarters appeared to be unoccupied during my visit.

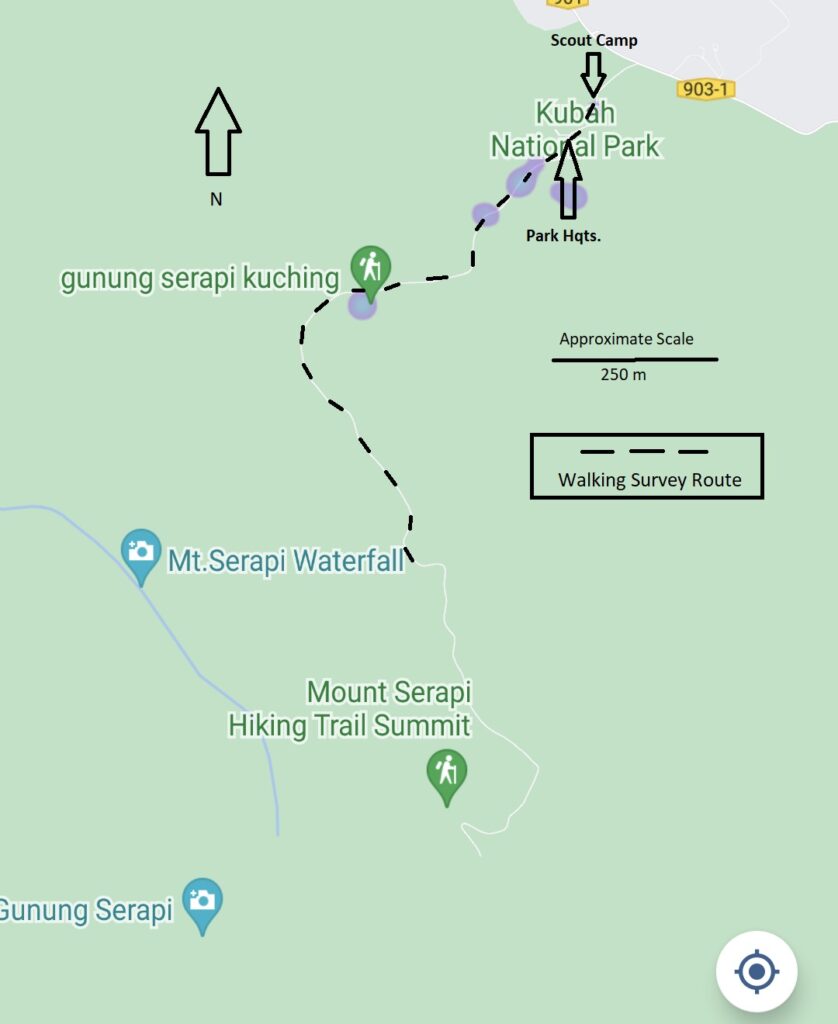

Kubah National Park, Sarawak (KNP, August 19, 2023: 0625-1200 hrs.)

Angela, the wonderful manager at Hotel Longhouse, kindly contacted Borneo Bird Tours regarding my intention to visit Kubah National Park. Arrangements were quickly made for a morning (half-day), professionally led bird trip to KNP. Julianna Sim, a local tour guide, would be meeting me at the hotel at 0600 hrs. and driving us to KNP for several hours of birding. The price, $650 MYR ($US 144), seemed rather high based on the low cost of living in Sarawak. My options were few. In fact, I either accepted their offer or went on my own. There were no other bird guides to be found in the area. I’m sure the company was aware of that.

Usually, I don’t mind birding new areas alone. Much of my field experience has been in Southeast Asia; the avifauna of Sarawak was largely familiar to me. However, finding the best birding location is often problematic. Local guides readily solve that issue, which results in finding more birds in less time than when birding alone. At the end of the day, I felt as though I had made the right choice. Julianna knew exactly where to go and largely what birds to expect. We had an exceptionally productive morning of birding in KNP.

Several bird species that we encountered in KNP were added to my trip list and would not be found anywhere else that I visited in Sarawak. These included, Brown-backed Needletail, two stunningly colorful broadbills, Banded Broadbill and Black & Yellow Broadbill; two Malkohas — Chestnut-breasted Malkoha and Raffle’s Malkoha and three new species of bulbul, Hairy-backed Bulbul, Spectacled Bulbul, and Gray-bellied Bulbul.

Aside from an impressive diversity of birds that we found in KNP, there were other natural wonders to be observed. Commonly seen on shady, roadside embankments, were clusters of pitcher plant Nepenthes ampullaria. These heterotrophic plants, presumably producing powerful protease enzymes for digesting organic material falling into them, also appear to support the reproductive life cycle of a tiny forest frog, recently discovered and described as Microhyla nepenthicola.

The miniature adult frogs vocalize, mate and deposit their egg clusters in the water-holding pitcher plants; the eggs hatching quickly into larvae that, rather than feed with their mouthparts in the usual tadpole fashion, derive nourishment from yolk stored in their gut. Their development into froglets is rapid and comparatively direct, abbreviating the typical lengthy, slow metamorphosis found in larger aquatic frog larvae. Then, the tiny froglets manage to climb out of the slippery walled pitcher plants and make their way to the moist leaf litter and streamside habitats in the forest.

Interesting questions remain regarding the relationship between the frog and the pitcher plant. Is it mutualistic, i.e. are both species deriving benefit? Is the relationship obligate or facultative? And what about the biochemistry? How is it that the frog eggs and larvae are not harmed or killed by the plants digestive enzymes?

I photographed some clusters of pitcher plants, hoping to later examine the images closely for identifiable content. All of the plants had rainwater; most had debris and possibly the remains of small arthropods inside. I couldn’t be certain if some of the plants contained frog eggs or larvae, since those would be quite small and translucent.

During our hike up the main road to the waterfall trailhead, Julianna pointed out a large, fast-moving column of insects on the forest floor. Initially, I believed they were driver ants (e.g. Dorylus sp.), rarely seen above ground. Using my cellphone I video-recorded them at close range. When reviewing the video, I was surprised to see that the insects were actually termites (Isoptera: Macrotermes sp.), an entirely separate lineage from ants (Hymenoptera), though remarkably convergent in terms of certain social behaviors. Welcome back to Entomology 101! Many, but not all of the termites, carried small clusters of whitish matter, composed of what probably was a particular type of fungus (Basidiomycota) used in their subterranean nests for digesting leaf litter into an edible product the termites could consume. Evidently, these fungus-farmers were relocating the colony, possibly due to flooding from recent heavy rainfall. Here’s a link to my termite video clip.

Sejingkat Power Station Ash Ponds (SAP, August 21, 2023: 0813-0926 hrs.)

Neither of us had been to this place and I wasn’t much help navigating from the hotel in Kuching. Mr. Bong, always a confident and competent driver, used his cellphone GPS and took us directly to the Sejingkat Power Station, located on the west bank near the mouth of the Sarawak River (see above map). From that point it was my job to find the birding spot, which was hidden from view by berms with shrubby second-growth. I walked westward on a weedy side road and soon found a mudflat with a large pipe gushing effluent. Hundreds of shorebirds were crowded together along a shallow, muddy stream created by the effluent. This was evidently the correct place; adjacent ash ponds and fields were mostly dry, overgrown with weeds and without shorebirds.

Julianna Sim had advised me to visit the ash ponds at high tide, when many shorebirds would be resting there. She said that at other times, there may be no birds at all; they would presumably be feeding on the outer bay mudflats. But the problem was that high tide would be in the late afternoon when rain was most likely. Mornings usually had favorable weather for birding and I made the decision to visit the ponds at ‘the wrong time,’ ignoring Julianna’s expert advice. At least I could find out where the site was and perhaps return on another day.

In fact, plenty of shorebirds were present at SAP when I arrived. They didn’t stay long, however. As soon as they spotted me creeping toward the pond with my camera, the birds were visibly agitated and began stretching their wings and nervously moving around. I quickly snapped a series of images from a distance of perhaps 60m, while trying to conceal myself partially in the bordering tall weeds. The birds weren’t fooled. Other visiting birders and local poachers (there was a mist net in a weedy field near the power plant) had likely tried the same trick. Within minutes of my arrival about half of the flock had departed; the remaining birds held on for another 20-30 minutes and I obtained a series of identifiable images of individual species.

Species that I could readily identify, included Terek Sandpiper (the most abundant bird there; nearly all in basic plumage), Curlew Sandpiper (about a dozen birds; most in transitional alternate – basic plumage), Common Redshank (transitional plumage), Black-tailed Godwit (transitional plumage), Red-necked Stint (alternate plumage) and Greater Sandplover (basic plumage). Further away, a pair of Little Tern (alternate plumage) was preening and then began circling the pond. This was great — all new bird species for my trip list and most of them would be documented with photos (see Annotated Bird List).

Buntal Mudflats, Sarawak (BMF, August 22, 2023: 1110-1150 hrs.)

I made a brief, mid-day survey of the Buntal shoreline, designated as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by international conservation agencies. At the time, there was a very low tide, exposing a broad stretch (80-120m) of mudflat extending more than 1km northward.

From Kampung Buntal, I walked out on a breakwater of large, angular rocks, then northward onto the mudflats (silt and sand), which supported dozens of shorebirds in the distance (see above photo). The substrate was generally firm and walkable, though occasional soft spots required caution. As expected, the birds moved off as I approached and my views of them were beyond 60m; in some cases more than 100m. I used the Nikon camera and 500mm lens in an effort to obtain identifiable images of the birds. Most of the species could be later identified by enlarging images on the computer monitor.

In addition to the shorebird species I had seen at Sejingkat (SAP), such as Terek Sandpiper and Greater Sandplover, there were two larger species that were fairly common here, though widely spaced, Eurasian Whimbrel and Eurasian Curlew. One comparatively large curlew may have been a Far-eastern Curlew; examination of my distant digital images were inconclusive for that species. In any case, it was noteworthy that I did not find any whimbrels or curlews at SAP.

Perhaps the best approach to birding the Buntal mudflats would be to hire a local fishing boat and cruise slowly along the shore at low tide. Otherwise, only distant views of the birds could be obtained from land, where a spotting scope would be essential.

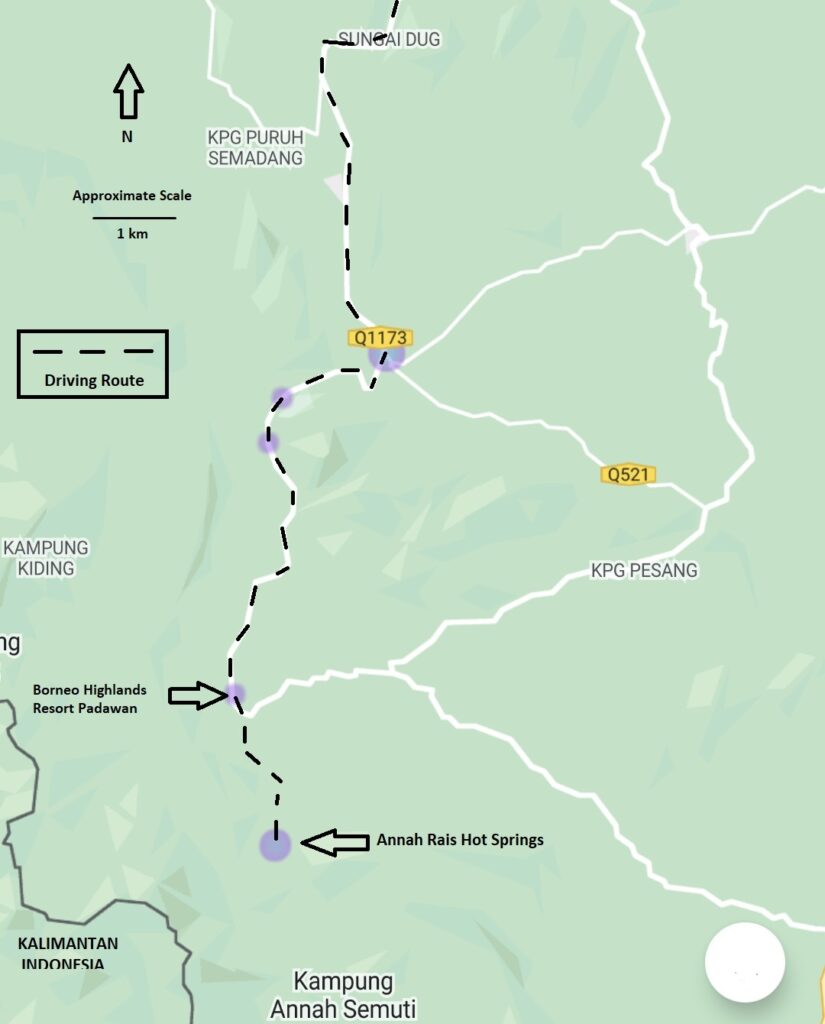

Borneo Highlands, including Annah Rais Hot Springs (ARHS, August 23 2023: 0830-1025 hrs.)

Due mostly to inclement weather, this was an unproductive day-trip into the Sarawak highlands bordering Kalimantan, Indonesia. It was raining when we left Kuching and raining intermittently everywhere else we went. We made a few stops to scan the countryside, including a potentially good birding spot on a bridge over a forested stream (Q1173 on the above map). But the rain kept us in the car most of the time, gazing out the window. When we arrived at our intended destination, the Borneo Highlands Resort, a guard informed us that the place was closed to the public. He offered no options, except to move along and find another location for birding.

About 1km south of the Borneo Highlands Resort, we turned right off the main highway onto a narrow mountain road leading to Annah Rais Kampung. Again, the rain kept us pinned down. About five kilometers further, we arrived at roadside tourist facility, Annah Rais Hot Springs. While waiting around in the car for a few minutes, the rains lessened, becoming an intermittent drizzle. That allowed me the first opportunity to walk around for a little birding. I ended up at on a covered veranda overlooking a rocky stream with masoned enclosures for bathing. Most of the secondary forest here had been removed and replaced by bamboo, then hacked down again. Exotic shrubs and weedy second-growth dominated the landscape. Birdlife was scarce.

Nevertheless, two new species for my trip list appeared briefly in small trees next to the veranda, Gray-hooded Babbler and Crimson-breasted Flowerpecker, both captured with blurry, yet identifiable photos.

When I hiked back up the trail to the roadside kiosk, Mr. Bong was sound asleep in the car. He appeared to be exhausted and in need of a good long rest. No objections from me. I sat down under a covered patio and reviewed a few photos from the day’s outing. Not much to show for the effort and expense. The day had been pretty much a wash. Suddenly, I felt a sharp burning sensation on my hand. A wasp had quickly stung me in a spot that I apparently had missed when covering exposed skin areas with insect repellent. A drop of blood oozed from the wound, located in the webbing between my fourth and fifth finger on the right hand.

No worries, I thought. The extractor kit in my backpack should easily remedy the problem. Within minutes I had the suction cup and plunger applied to the wound. In my haste I had chosen a suction cup that was too large. I clumsily switched it for the smallest one in the kit. Same problem. The location of the sting at the base of the two fingers would not allow the suction cup to fit securely. The device, usually quite reliable and effective when used within a few minutes of a bite or sting, in this case was useless. The only treatment possible would be to manually squeeze blood and venom from the wound and clean the affected area with an alcohol swab. Unfortunately, that didn’t work either.

Pain from the sting wound intensified, combined with redness and swelling. Within minutes, the fourth and fifth fingers of my right hand were numb and nearly useless. I focused on steady breathing. Everyone knows there are a thousand ways to die in Borneo. Maybe I just discovered an additional one. No big deal. Dude, just man-up.

Oh, I forgot to mention another affliction suffered by zoologists. We tend to rationalize and explain the most minute trivia in nature. Whatever sort of neurotoxin this little hymenopteran had injected into my epidermal tissue, it was having a significant and lasting inflammatory effect. Forty-eight hours later, the swelling decreased and I regained full use of my hand. This was the first time, counting multiple previous applications, that the Extractor device failed me; it was a painful yet valuable lesson that not all bites and stings may be treatable using an extractor device of this type (see accompanying photo). Gee, that’s a comforting thought. Anyway, I guess nobody really knows when their time’s up. At least in my case it should happen properly with my boots on.

Permai Rainforest Resort (PRR, August 24-29, 2023)

Following an initial visit and booking at the Permai Rainforest Resort (PRR) on August 22, I relocated here for six consecutive days (August 24-29), prior to my departure from Sarawak on August 30, 2023. While residing at the resort, I made daily walking surveys for birds and other wildlife, using the boardwalks and trails. My surveys usually included the adjacent Damai Resort parking area bordered by the contiguous mature rainforest with PRR, together with the Kampung Budaya gardens and public beach-picnic area. I also spent time on the observation deck of my treehouse room. There, warm afternoons were productive for wildlife, which included two new species of lizard for my trip list, Green Crested Lizard (Bronchocela cristatella) and Bornean Tree Skink (Apteryogodon vittatum). Two more arboreal species were also found at PRR, Five-banded Flying Lizard (Draco quinquefasciatus) and Garden Flying Snake (Chrysopelea paradisi). An individual of the latter species landed briefly on the front porch of my treehouse room as I was leaving with all my packed belongings (including camera gear) on the last morning of my stay at the resort.

In that way, my surveys sampled the available habitats in the area, including coastal waters, shoreline, riparian and mangrove forest, lowland dipterocarp forest, gardens, lawns, parkland and ruderal fields with scattered casuarina trees and ornamental vegetation adjacent to second-growth in various stages. Taken together, the daily surveys through these varied habitats, resulted in the addition of about ten bird species and four arboreal reptile species to the trip list.

A troupe of about eight Proboscis Monkey and another of at least twenty Silvered Leaf Monkey were seen regularly at the resort. These animals covered large areas of the Permai forest and were never found at the same location on consecutive days. Both species frequented fruiting trees, though the latter’s diet was largely foliage as its name suggests. Additionally, fruiting trees attracted Plantain Squirrel and a variety of birds, including barbets, bulbuls, leafbirds, sunbirds and flowerpeckers. Hornbills, as mentioned earlier, were conspicuously absent.

There were some interesting behavioral differences between the Silvered Leaf Monkey and Proboscis Monkey at the resort. While both species kept mostly to the tree canopy, the Silvered Leaf Monkey commonly descended onto roof tops and seemed fairly well habituated to humans. In contrast, Proboscis Monkeys kept their distance from people and were never observed climbing on or near buildings. I suspect that, of the two species, the endemic and endangered Proboscis Monkey has suffered the greatest hunting pressure. Its comparatively shy behavior certainly suggests an historically unpleasant relationship with humans.

Both species displayed remarkable speed and agility in the trees; this was especially apparent for the comparatively large and bulky Proboscis Monkey. A full grown male, with an outsized belly and matching snout, while watching me photographing him from the ground below, suddenly leaped to an adjacent tree and, within a few seconds was entirely out of my view. Unlike the Silvered Leaf Monkey, though, adult male and female Proboscis Monkeys appeared to be solitary, maintaining visual contact with their cohorts in separate trees.

Biologists speculate as to the adaptive significance of an extraordinarily large nose of the Proboscis Monkey, particularly in older males. There seems to be general agreement that the outsized, Kilroy-was-here-nose is used as both a resonating chamber for amplifying vocalizations and for intimidating other, younger males. Interestingly, I did not see any aggressive encounters among Proboscis Monkeys, nor hear any of their vocalizations.

Another feature of this species is an enlarged belly which includes a multi-chambered stomach for digestive efficiency of plant material. As with cattle and other herbivores, regurgitation of partially digested material allows for multiple rounds of processing. I’m guessing that vocalizing with such a heavily industrialized digestive system must require an extraordinary effort and thereby commands due respect from the audience.

A motorboat trip was arranged by the resort for the morning of August 26, to visit the coastal waters of Santubong, including mangroves and a Malay island village, Kampung Salak. I learned about the trip only thirty-minutes before the scheduled departure and quickly made a booking ($165 MYR). Two other resort guests and myself, together with Captain Junai-di, and Seaman First Class, Marcello, would be the only folks on the 7m long, fiberglass skiff, powered by a Honda 75 hp outboard motor.

This was an especially productive trip for birds and other wildlife, including two pods of 4-5 Irrawaddy Dolphin, a life-mammal for three of us. This peculiar, euryhaline mammal is an endangered species found sparingly in the shallow bays, mangrove estuaries and rivers from the Bay of Bengal through Southeast Asia. We were able to approach these animals slowly and quietly in a mangrove channel, averaging about 5m in depth. Although these dolphins are essentially blind, their hearing and echolocation are excellent. Most likely they were well aware of our presence. Young ones followed the adults closely. Adults occasionally sprayed water with their mouths, showed their tails and dove for several minutes. They were strong swimmers and often surfaced 50-80m from their point of entry.

These mangroves are also home to the legendary, man-eating Saltwater Crocodile. An individual basking onshore was approachable for clear views and photos while we remained safely in the boat. Earlier, a much larger pair (4-5m in length) was seen onshore; both of them bolted into the water when approached by several other tour boats. Evidently, locals hunt these animals for the meat and skins. Otherwise the formidable beasts have little to fear; they are at the top of the food chain. And if anyone happens to be swimming in the area or fall out a tour boat, they are eagerly added to the menu.

The final segment of the boat trip was especially exciting for me. An optional detour was initially suggested by the captain; the rest of us nodded with approval. My two companions from the Netherlands, both secondary school teachers (English and Philosophy) were politely amused, though I’m fairly sure had reached their quota for birds. Our boat captain’s eyes had lit up when seeing my interest in birds. He had a little surprise in mind. We sped out of mangroves and set a course due north into the open ocean. The boat began taking a bit of a pounding in the choppy seas. For the first time on the trip, I was looking around for the life jacket that I was supposed to be wearing.

Soon, we arrived at a small, rocky island inhabited by hundreds of Bridled Tern and lesser numbers of Black-naped Tern. We circled the island slowly and I went wild with the camera. Birds on the rocks, birds in flight above and below, birds everywhere. Incredible! Considering the numbers and great mobility of these terns, I wondered why I had not seen a single one from the shore at PRR. Indeed, if we hadn’t gone out to this island, I would have missed them entirely on this trip. Additionally, as we approached the island, I caught a glimpse of a Streaked Shearwater, and managed a couple of very blurry but identifiable photos. That was another unexpected seabird for my trip list. Yes! Altogether, an amazingly productive journey in the coastal waters of Santubong.

At the conclusion of the trip, the three of us were quite satisfied with our little adventure and agreed to give the crew a respectable tip ($20 MYR each), which they both appeared to greatly appreciate.

Annotated Bird List for Sarawak, East Malaysia, 16-29 August 2023 Callyn Yorke

Abundance: Numbers following each species entry are the highest count for a single survey, when multiple surveys were made. The location (see below) with the highest numerical abundance is listed first in the species accounts.

Age, sex and molt (when known): ad = adult; imm = immature; m = male; f = female; bsc plmg = basic (non-breeding plumage; alt plmg = alternate (breeding) plumage; trans = transitional plumage, i.e. alternate into basic plumage.

Frequency and Distribution (C, UC, in reference to specific areas (see below) receiving multiple surveys) : C = Common, i.e. found during half or more of the surveys ; UC = found in less than half of the surveys; ubiq. = ubiquitous in appropriate habitat.

Survey Location Abbreviations: PRR = Permai Rainforest Resort and adjacent area; KWF = Kuching Waterfront; HLH = Hotel Longhouse neighborhood; SBG = Sarawak Botanical Garden, Kuching; OP = Orchid Park, Kuching; KRP = Kuching Reservoir Park; SNHM = Sarawak Natural History Museum grounds; BCM = Borneo Cultures Museum grounds; SNR = Semenggoh Nature Reserve; BNP = Bako National Park; BI = Bird Island; KNP = Kubah National Park; BH = Borneo Highlands; ARHS = Anna Rais Hotsprings; SAP = Senjingkat Ash Ponds; BMF = Buntal Mudflats.

Ecology and Behavior: aerial insect hawking (ah); taking fruit, berries or parts of flowers (fr); gleaning insects from foliage (ig); probing into surface (pr); estimated height (m) above ground (agl); gregarious (greg); mixed-species flock (msf).

Systematics and Nomenclature used herein, is an amalgam of Avibase, International Ornithological Congress (IOC) and current (2023) online resources, i.e. Birds of the World, Cornell University, USA.

Borneo endemics and near-endemics are listed in Bold Face lettering.

- Feral Rock Pigeon Columba livia 20 greg. in small flocks on buildings and on pavement and in vacant lots, often with other species, e.g. ESDO, HLH, KWF, C, ubiq.

- Eastern Spotted Dove Spilopelia chinensis 10 vocal, greg. pairs often on ground and in tall trees, C, ubiq.

- Zebra Dove Geopelia striata 8 vocal, greg. pairs and trios on pavement and ground in weedy vacant lots, C, ubiq.

- Pink-necked Green Pigeon Treron vernans 6 greg. shy and easily flushed; small flocks frequenting the canopy of tall fruiting trees (e.g. Ficus spp.), C, ubiq.

- Thick-billed Green Pigeon Treron curvirostra 2 a pair in the canopy of a tall, fruiting fig, SNR.

- Gray-rumped Treeswift Hemiprocne longipennis 2 a pair circling a large clearing and parking area, 20m agl, UC PRR.

- Brown-backed Needletail Hirundapus giganteus 1 flying 1 – 5m agl, back and forth over an open, weedy clearing in the forest, KNP.

- Western Glossy Swiftlet Collocalia affinis 2 a pair flying erratically, bat-like over the forest and adjacent clearing, 2 – 5m agl, KNP.

- Black-nest Swiftlet Aerodramus maximus 12 greg. circling at 5 -30m agl over parkland habitat outside of BCM.

- Swiftlet Aerodramus fuciphagus. c.f. germani 25 most individuals showing a conspicuous buffy rump patch, greg. flying 1 -10m, back and forth over an open, weedy fields, shorelines ,coastal scrub and second-growth, C, ubiq.

- Asian Palm Swift Cypsiurus balasiensis 3 flying fast at dawn and dusk, over and through second-growth coastal forest, UC, PRR.

- Greater Coucal Centropus sinensis 2 vocal, secretive; individuals flushed from dense cover in tall grass and second-growth, C, ubiq.

- Lesser Coucal Centropus bengalensis 1 repeatedly vocal, noted the coucal’s comparatively small size when flushed from tall grass and second-growth at edge of an open area next to the Budaya kampung main beach and picnic area, UC, PRR.

- Raffle’s Malkoha Rhinortha chlorophaea 1 hopping around in the subcanopy of a tall forest tree at the edge of a clearing, KNP (photo).

- Black-bellied Malkoha Phaenicophaeus diardi 1 subsequently identified by a distant image I obtained of a previously unidentified bird in the canopy of a 25m tall fruiting tree, gallery forest; the same tree had moments earlier attracted an Oriental Hornbill, SNR.

- Chestnut-breasted Malkoha Phaenicophaeus curvirostris 1 shy and secretive in the dense foliage of trees at the edge of a clearing, KNP.

- Western Koel Eudynamys scolopaceus 1 well concealed and repeatedly vocal, then moving to another tree bordering OP.

- Plaintive Cuckoo Cacomantis merulinus 1 repeatedly vocal (unseen) in second-growth and trees bordering a weedy clearing, UC, PRR.

- White-breasted Waterhen Amaurornis phoenicurus 1 scurrying across open areas into dense cover near water, KRP, SBG, SAP.

- Streaked Shearwater Calonectris leucomelas 1 long winged with dark brown upperparts; identification subsequently confirmed with images I obtained from the boat (none in sharp focus); the bird was flying 1-3m over the ocean surface, loosely associated with BRTE, BI.

- Striated Heron Butorides striata 1 individual adults on shore, quickly seeking cover, UC PRR; BMF.

- Intermediate Egret Ardea intermedia 2 individuals foraging in large, grassy fields and drainages, ubiq.

- Greater Sandplover Charadrius leschenaultii 4 bsc. and trans. plmg., individuals on mudflats, loosely associated with other shorebirds, SAP, BMF.

- Eurasian Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus 5 bsc. plmg. individuals foraging, widely spaced on mudflats, BMF (photo).

- Eurasian Curlew Numenius aequata 3 bsc. plmg. individuals foraging, widely spaced on mudflats, BMF.

- Eastern Black-tailed Godwit Limosa melanurioides 7 trans. plmg. individuals associated with other shorebirds, SAP (photo).

- Broad-billed Sandpiper Calidris falcinellus 1 bsc. plmg. an individual foraging alone on distant mudflat, BMF.

- Curlew Sandpiper Calidris ferruginea 12 trans. plmg. loosely greg. with other shorebirds, e.g. TESA, SAP (photo).

- Red-necked Stint Calidris ruficollis 5 alt. and trans. plmg. greg. loosely associated with other shorebirds e.g. TESA, SAP, BMF.

- Sanderling Calidris alba 1 trans. plmg. foraging alone on mudflat, BMF (photo).

- Terek Sandpiper Xenus cinereus 160 most in bsc. a few trans. plmg. highly greg. and associated with other shorebirds, e.g. CUSA and CORE, SAP, BMF (photo).

- Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos 2 bsc. plmg., individuals foraging on shorelines and edges of ponds, drainages, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Common Redshank Tringa totanus 15 trans. plmg. greg. with other shorebirds, SAP (photo).

- Marsh Sandpiper Tringa stagnatilis 2 bsc. plmg. in msf with other shorebirds, SAP.

- Bridled Tern Onychoprion anaethetus 160 (conservative. est.) ad. (alt. & bsc. plmg., imm. ) highly greg., loosely associated with BNTE on and around BI (photo).

- Little Tern Sternula albifrons 2 (alt. plmg.) a pair preening then flying around ash pond, SAP (photo).

- Common Gull-billed Tern Gelochelidon nilotica 1 on bank of adjacent mangrove channel, then in flight, BMF.

- Whiskered Tern Chlidonias hybrida 4 (alt plmg.) greg on mudflats before taking flight, BMF.

- Black-naped Tern Sterna sumatrana 60 ad., imm. (alt., bsc. plmg.) greg. pairs in flight and resting in small flocks on low, peripheral rocks, spatially separated from BRTE, BI (photo).

- Greater Crested Tern Thalasseus bergii 4 loosely gregarious in low, circling flight over shallow mangrove bays near Kmpg. Salak (boat trip).

- Brahminy Kite Haliaster indus 3 (ad, imm) circling 60-80m above SBG.

- Oriental Pied Hornbill Anthracoceros albirostris 1 flying to emergent fruiting tree in gallery forest, SNR.

- Blue-throated Bee-eater Merops viridis 2 sallying from utility wires and mid-level tree limbs at the edge of weedy fields and clearings; flying over town early one morning, UC, HLH; KNP.

- Stork-billed Kingfisher Pelargopsis capensis 1 diving into weedy drainage (not seen capturing anything), then perching at low and mid-level in adjacent trees, SBG (photo).

- Collared Kingfisher Todiramphus chloris 1 individuals perched in trees near water, UC, KWF; SBG.

- Bornean Barbet Psilopogon eximus 1 in fruiting fig tree above resort cafe, msf with RCBA and OWBU, UC, PRR.

- Red-crowned Barbet Psilopogon rafflesii 3 vocal, individuals and pairs, often in msf with bulbuls and leafbirds, frequenting fruiting trees, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Buff-rumped Woodpecker Meiglyptes grammithorax 1 (m) foraging in subcanopy of tree next to resort cafe, UC, PRR.

- Blue-crowned Hanging Parrot Loriculus galgulus 2 (m,f) individuals and pairs foraging in canopies of flowering and fruiting trees at edge of forest and in parks, KNP; SBG; UC, PRR (photo).

- Common Long-tailed Parakeet Psittacula longicauda 2 a pair engaged in courtship head-bobbling displays while atop a tall, tree trunk with nest cavity holes; one of the pair entering and exiting a nest cavity; located across the roadway at the entrance of OP (photo).

- Banded Broadbill Eurylaimus harterti 2 a pair in adjacent trees at mid-level of the forest edge in the scout camp, KNP (photo).

- Black and Yellow Broadbill Eurylaimus ochromalus 2 a pair at upper and mid levels of forest edge trees in the scout camp, KNP (photo).

- White-breasted Woodswallow Artamus leucorhynchus 2 often seen perched on and sallying from utility wires in large clearings, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Common Iora Aegithina tiphia 3 (m,f) vocal, greg. foraging in canopies of tall shrubs and trees, C, ubiq.

- Green Iora Aegithina viridissima 2 foraging in low canopies of flowering and fruiting trees, UC, PRR.

- Great Iora Aegithina lafresnayei 1 foraging in msf with COIO in tree canopies at the edge of a clearing, UC, PRR.

- Sunda Pied Wagtail Rhipidura javanica 2 often in msf with several species, middle to upper levels in second-growth and forest edge, C, ubiq.

- Greater Racquet-tailed Drongo Dicrurus paradiseus 2 flying across small forest clearing, KNP.

- Oriental Paradise Flycatcher Tersiphone affinis 1 (f) attracted briefly to playback of its vocalizations, roadside forest, KNP.

- Sunda Long-tailed Shrike Lanius bentet 1 snatched large insect from lawn, UC, KWF; also commonly seen perched on utility wires in and outside of Kuching.

- Bornean Black Magpie Platysmurus aterrimus 4 vocal, greg. wary and shy, staying in subcanopy of tall trees, UC PRR; KNP; SBG (photo).

- Yellow-bellied Prinia Prinia flaviventris 1 vocal at edge of wet, grassy clearing, KNP; SAP.

- Rufous-tailed Tailorbird Orthotomus sericeus 2 vocal, responding to playback recordings of its vocalizations, active in second-growth in clearings, KNP (photo).

- Ashy Tailorbird Orthotomus ruficeps 2 vocal, secretive at weedy edge of clearings with second-growth, drainages and ponds, C, ubiq..

- House Swallow Hirundo javanica 2 pairs on utility wires and flying low over fields, towns and wetlands, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Hairy-backed Bulbul Tricholestes criniger 1 perched briefly on lower limb of fruiting tree in clearing, loosely associated with several other bulbul species, scout camp, KNP (photo).

- Streaked Bulbul Ixos malaccensis 2 often in msf with other bulbul species in fruiting trees, C, PRR; KNP.

- Spectacled Bulbul Ixidia erythropthalmos 1 in fruiting tree with msf of other bulbuls and RCBA, scout camp, KNP (photo).

- Sunda Yellow-vented Bulbul Pycnonotus analis 5 vocal, greg. often in msf with leafbirds, barbets and other bulbul species in flowering and fruiting trees, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Olive-winged Bulbul Pycnonotus plumosus 6 vocal, greg. pairs in flowering/fruiting shrubs and trees, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Red-eyed Bulbul Pycnonotus brunneus 2 greg. pairs in second-growth and fruiting trees with other bulbul species, e.g. OWBU, C, ubiq.

- Black-headed Bulbul Brachypodius atriceps 2 in fruiting tree with RCBA and OWBU, scout camp, KNP (photo).

- Bold-streaked Tit-babbler Mixornis bornensis 2 active, ig. in low to mid-levels of second-growth and shady forest edge, BNP, C, PRR (photo).

- Gray-hooded Babbler Cyanoderma bicolor 2 greg. pairs active in low to mid-level in second-growth and forest edge, UC, PRR; ARHS.

- Common Myna Acridotheres tristis 12 vocal, greg. several paired birds molting head feathers, giving the appearance of being almost bald-headed; often with JAMY on pavement and lawns, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Javan Myna Acridotheres javanicus 10 greg. pairs often foraging on lawns and in vacant lots with COMY, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Common Hill Myna Gracula religiosa 2 greg. pairs perched together on high, horizontal tree limbs; not seen on ground, KNP, SBG, UC, PRR.

- Asian Glossy Starling Aplonis panayensis 120 (ad, imm) vocal and highly greg. flocks (10 -40 individuals) in areas with multiple fruiting trees; not seen on the ground, C, ubiq.

- Oriental Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis 2 vocal, shy and rather secretve in trees at edges of clearings, BNP, SBG, UC PRR.

- White-rumped Shama Copsychus malabarica 1 (f) lower-mid level of forest edge, UC PRR.

- Verditer Flycatcher Eumyias thalassinus 1 canopy perch at edge of clearing, scout camp, KNP.

- Asian Fairy-bluebird Irena puella 2 (m,f; imm) vocal, greg. pairs in fruiting trees at the edge of the forest, often in msf with barbets, bulbuls and leafbirds, C, PRR; BNP, KNP, SBG.

- Greater Green Leafbird Chloropsis sonnerati 2 (m,f) in fruiting trees, msf with bulbuls and barbets, C, PRR; KNP (photo).

- Lesser Green Leafbird Chloropsis cyanopogon 2 in fruiting tree, msf with bulbuls and barbets, scout camp, KNP; UC, PRR.

- Crimson-breasted Flowerpecker Prionochilus percussus 1 (f) in second-growth at edge of stream, ARHS.

- Orange-bellied Flowerpecker Dicaeum trigonostigma 2 (m,f) vocal, greg. pairs in flowering and fruiting shrubs and trees, forest edge, gardens and second-growth, C, ubiq..

- Little Spiderhunter Arachnothera longirostra 1 briefly visiting bird-of-paradise flowers in clearing around treehouse, UC, PRR (photo).

- Yellow-eared Spiderhunter Arachnothera chrysogenys 2 frequenting inflorescences of a forest edge tree, UC, PRR.

- Brown-throated Sunbird Anthreptes malacensis 4 (m,f) vocal, greg. pairs alternating on flowering and fruiting shrubs and trees, C, ubiq. (photo).

- Lesser Crimson Sunbird Aethopyga siparaja 1 (m) briefly in a decorative shrub at the edge of OP.

- Dusky Munia Lonchura fuscans 3 greg. in tall grass, second-growth and trees at edge of clearings, KNP; UC, PRR (photo).

- Scaly-breasted Munia Lonchura nisoria 4 greg. flushed from tall grass in clearing, SBG.

- Chestnut Munia Lonchura atricapilla 4 (ad., imm) greg. in tall, seeded grass at edge of roadway, SAP (photo).

- Eurasian Tree Sparrow Passer montanus (m,f) vocal, greg. disturbed and developed areas, on pavement and buildings, vacant lots, C, ubiq.